图书馆:铜

{{Elementbox

|name=铜 |enname=copper |number=29 |symbol=Cu |left=镍 |right=锌 |above=- |below=银 |series=过渡金属 |series comment= |group=11 |period=4 |block=d |series color= |phase color= |appearance=红橙色带金属光泽 |image name=NatCopper.jpg |image size= |image name comment=纯铜 |image name 2= |image size 2= |image name 2 comment= |atomic mass=63.546 |atomic mass 2=3 |atomic mass comment= |electron configuration=[氩] 3d10 4s1 |electrons per shell=2,8,18,1 |color= |phase= |phase comment= |density gplstp= |density gpcm3nrt=8.96 |density gpcm3nrt 2= |density gpcm3mp=8.02 |melting point K=1357.77 |melting point C=1084.62 |melting point F=1984.32 |melting point pressure= |sublimation point K= |sublimation point C= |sublimation point F= |sublimation point pressure= |boiling point K=2835 |boiling point C=2562 |boiling point F=4643 |boiling point pressure= |triple point K= |triple point kPa= |triple point K 2= |triple point kPa 2= |critical point K= |critical point MPa= |heat fusion=13.26 |heat fusion 2= |heat fusion pressure= |heat vaporization=300.4 |heat vaporization pressure= |heat capacity=24.440 |heat capacity pressure= |vapor pressure 1=1509 |vapor pressure 10=1661 |vapor pressure 100=1850 |vapor pressure 1 k=2089 |vapor pressure 10 k=2404 |vapor pressure 100 k=2834 |vapor pressure comment= |crystal structure=面心立方 |oxidation states=+1、+2、+3、+4 |oxidation states comment= |electronegativity=1.90 |number of ionization energies=4 |1st ionization energy=745.5 |2nd ionization energy=1957.9 |3rd ionization energy=3555 |4th ionization energy= |atomic radius=128 |atomic radius calculated= |covalent radius=132±4 |Van der Waals radius=140 |magnetic ordering=抗磁性[1] |electrical resistivity= |electrical resistivity at 0= |electrical resistivity at 20=1.678×10-8 |thermal conductivity=401 |thermal conductivity 2= |thermal diffusivity= |thermal expansion= |thermal expansion at 25=16.5 |speed of sound= |speed of sound rod at 20= |speed of sound rod at r.t.=3810 |Tensile strength= |Young's modulus=110-128 |Shear modulus=48 |Bulk modulus=140 |Poisson ratio=0.34 |Mohs hardness=3.0 |Vickers hardness=343–369 |Brinell hardness=235–878 |CAS number=7440-50-8 |isotopes= {{Elementbox isotopes stable | mn=63 | sym=Cu | na=69.15% | n=34 }} {{Elementbox isotopes decay | mn=64 | sym=Cu | na=人造 | hl=12.7 小时 | dm1={{衰变|ε}} | de1=- | pn1=64 | ps1=镍 | dm2={{衰变|β-}} | de2=- | pn2=64 | ps2=锌 }} {{Elementbox isotopes stable | mn=65 | sym=Cu | na=30.85% | n=36 }} {{Elementbox isotopes decay | mn=67 | sym=Cu | na=人造 | hl=61.83 小时 | dm1={{衰变|β-}} | de1=- | pn1=67 | ps1=锌 }} }} {{about|化学元素铜,口语俗称“红铜”或者“紫铜”|口语中俗称为“铜”的黄色合金|黄铜}} 铜({{标音|拼音=tónɡ|注音=ㄊㄨㄥˊ|粤拼=tung4}};{{lang-en|Copper}}),俗称红铜或者紫铜,是最早发现的化学元素,其化学符号为{{化学式|铜}}(源于{{lang-la|cuprum}}[2]),原子序数为29,原子量为{{val|63.546|u=u}}。纯铜是柔软的金属,表面刚切开时为红橙色带金属光泽、延展性好、导热性和导电性高,因此在电缆、电气和电子元件是最常用的材料,也可用作建筑材料,以及组成众多种合金,例如用于珠宝的纹银,用于制作船用五金和硬币的白铜以及用于应变片和热电偶的康铜。铜合金机械性能优异,电阻率很低,其中最重要的是青铜和黄铜。此外,铜也是耐用的金属,可以多次回收而无损其机械性能。

铜是在自然界中可以直接使用的金属的其中一种(天然金属),这使得其在公元前8000年时被多个不同地区的的人们使用,在数千年之后,铜在公元前5000年成为首个从硫化矿石中冶炼出的金属;在公元前4000年成为第一个在模具中塑形的金属,更在公元前3500年与另一种金属锡锻造成了人类史的第一个合金——青铜[3]。在古罗马时期,铜矿大多在塞浦路斯开采,同时也使这种金属得到最初的名字сyprium(也就是塞浦路斯的金属),之后演变为сuprum(拉丁语),而现在常用的copper则是于公元1530年前后第一次被使用[4]。

铜在自然界中经常形成二价的铜盐类,它们使蓝铜矿、孔雀石和绿松石等矿物具有蓝色或绿色,并且在历史上也广泛用作颜料。氧化成铜绿的铜经常被用在建筑物的屋顶上。而有时铜也被用在装饰艺术上,而且不管是元素型态或形成化合物的铜都会被利用。另外,铜化合物用作抑菌剂、杀真菌剂和木材防腐剂。

铜是所有生物所必需的微量膳食矿物质,因为那是呼吸酶复合体-细胞色素c氧化酶(cytochrome c oxidase)的重要组成成分。在软体动物和甲壳类动物中,铜是组成血液色素血蓝蛋白(blood pigment hemocyanin)的成分,而在鱼类或其他脊椎动物中,则被铁血红蛋白复合体给取代。另外,在人体中,铜主要分布在肝脏、肌肉和骨骼中[5],而一般成人每公斤体重约含有1.4至2.1毫克的铜[6]。

性质

[编辑]物理性质

[编辑]

铜位于元素周期表第11族,同族的还有银和金,这些金属的共同特点有延展性高、导电性好。这些元素的原子最外层只有一个电子,位于s亚层,次外层电子d亚层全满。原子间的相互作用以s亚层电子形成的金属键为主,而全满的d亚层的影响不大。与d亚层未满的金属原子不同,铜的金属键共价成分不多,而且很弱,所以单晶铜硬度低、延展性高。[7] 宏观上,晶格中广泛存在的缺陷(如晶界),阻碍了材料在外加压力下的流动,从而使硬度增加。因此,常见的铜是细粒多晶,硬度比单晶铜更高。[8]

铜不但柔软,导电性(59.6×106 S/m)、导热性(401 W/(m·K))也好,室温下在金属单质中仅次于银。[9]这是因为室温下电子在金属中运动的阻力主要来自于电子因晶格热振动而发生的散射,而较柔软的金属散射则较弱。[7]铜在露天环境下所允许的最大电流密度为3.1×106 A/m2(横截面),更大的电流就会使之过热。[10]像其他金属一样,铜和其他金属并置会发生{{link-en|电化腐蚀|galvanic corrosion}}。[11]

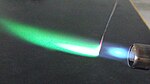

铜是四种天然色泽不是灰色或银色的金属元素之一,另外三种是铯、金(黄色)和锇(蓝色)。[12]纯净的铜单质呈橙红色的,接触空气以后失去光泽而变红。铜的这种特殊颜色是由于全满的3d亚层和半满的4s亚层之间的电子跃迁——这两个亚层之间的能量差正好对应于橙光。铯和金呈黄色也是这个原理。[7]

化学性质

[编辑]

铜不和水反应,但和空气中的氧气缓慢反应,形成一层棕褐色的氧化铜,但和铁暴露在潮湿空气中形成铁锈不同,铜锈能保护下面的铜免受进一步腐蚀。铜质建筑物(如自由女神像)上常可见到一层铜绿(碱式碳酸铜)[13]铜接触硫后因生成各种硫化物而失去光泽。[14]铜的氧化态有0、+1、+2、+3、+4,其中+1和+2是常见氧化态。+3氧化态的有六氟合铜(III)酸钾,+4氧化态的有六氟合铜(IV)酸铯,0氧化态的Cu(CO)2可通过气相反应再用基质隔离方法检测到[15]。

铜容易被卤素、互卤化物、硫、硒腐蚀,硫化橡胶可以使铜变黑。铜在室温下不和四氧化二氮反应,但在硝基甲烷、乙腈、乙醚或乙酸乙酯存在时,则生成硝酸铜:

- Cu + 2 N2O4 → Cu(NO3)2 + 2 NO

金属铜易溶于硝酸等氧化性酸,若无氧化剂或适宜配位试剂的存在时,则不溶于非氧化性酸,如:

- 铜和硝酸的反应如下:

- 3 Cu + 8 HNO3(稀) → 3 Cu(NO3)2 + 2 NO↑ + 4 H2O

- Cu + 4 HNO3(浓) → Cu(NO3)2 + 2 NO2↑ + 2 H2O

- 和浓硫酸的反应为:

- Cu + 2 H2SO4(浓) → CuSO4 + SO2↑ + 2 H2O

- 和浓硫酸的反应产物还和温度有一定关系。反应过程中硫酸逐渐变稀,直到反应停止。铜不能和稀硫酸反应,但是有氧气存在时,按下式反应:

- 2 Cu + O2 + 2 H2SO4 —Δ→ 2 CuSO4 + 2 H2O

- 3 Cu + 6 H+ + ClO3− → 3 Cu2+ + Cl− + 3 H2O

- 存在硫脲时发生配位反应:

- 2 Cu + 6 S=C(NH2)2 +2 HCl → 2Cu(I)(S=C(NH2)2)3Cl + H2[16]

- 2 Cu + 8 HCl(浓) → 2 H3[CuCl4] + H2↑

铜在酸性条件下能和高锝酸根离子反应,使高锝酸根离子还原为单质锝:

- 7 Cu + 2 TcO4- + 16 H+ → 2 Tc + 7 Cu2+ + 8 H2O[18]

- 2 Cu + FeS → Cu2S + Fe

铜加热可以和三氧化硫反应,主要反应有两种:

- 4 Cu + SO3 → CuS + 3 CuO

- Cu + SO3 → CuO + SO2

铜在干燥空气中稳定,可保持金属光泽。但在潮湿空气中,表面会生成一层铜绿(碱式碳酸铜,分子式:Cu2(OH)2CO3),保护内层的铜不再被氧化。反应方程式:

- 2 Cu + O2 + CO2 + H2O → Cu2(OH)2CO3

同位素

[编辑]{{Main|铜的同位素}} 铜有29个同位素。63Cu和65Cu很稳定,63Cu在自然存在的铜中约占69%;它们的自旋量子数都为3/2。[19]其他同位素都有放射性,其中最稳定的是67Cu,半衰期61.83小时。[19]已确定7个亚稳态核素的特性,其中68mCu半衰期最长,为3.8分钟。质量数64以上的核素发生β衰变,质量数64以下的核素发生正电子发射。64Cu两种衰变都会发生,半衰期12.7小时。[20]

62Cu和64Cu有重要应用。62Cu在62Cu-PTSM中用作正电子发射断层扫描的放射性示踪剂。[21]

存在

[编辑]铜在巨型恒星中生成[22],在地壳中丰度约为50 ppm[23],存在形式为自然铜,硫化物矿(黄铜矿和辉铜矿和铜蓝),硫代酸盐矿物(砷黝铜矿和异铜),碳酸铜矿(蓝铜矿和孔雀石),还有氧化亚铜矿(赤铜矿)跟氧化铜矿(黑铜矿Tenorite {{Wayback|url=https://en.wikipedia.hfut.cf/wiki/Tenorite |date=20200208232157 }})。[9]已知的最大一块单质铜重420吨,在1857年于美国密歇根州{{link-en|凯韦诺半岛|Keweenaw Peninsula}}发现。[23]自然铜是一种多晶,记录到的最大的单晶尺寸为4.4×3.2×3.2厘米。[24]

生产

[编辑]{{see also|各国铜产量列表}} 铜在地壳中的含量约为0.01%。大部分铜都是从斑岩铜矿中{{link-en|露天开采|open-pit mining}}{{link-en|提取铜的方法|Copper extraction techniques|提取}}的。这种铜矿含有0.4%到1.0%的铜。智利的丘基卡马塔,美国犹他州的宾厄姆峡谷矿和美国新墨西哥州的{{link-en|奇诺矿|Chino Mine}}就是这种铜矿。根据英国地质调查局(BGS)统计,2005年智利铜矿产量最高,占到全球产量三分之一强,接下来是美国、印度尼西亚和秘鲁。[9]铜也可由{{link-en|原地浸出|In situ leach}}法开采,亚利桑那州的几个铜矿是这种方法的首选。[25]铜的使用量还在增加,而可开采量仅能满足所有国家达到发达国家的使用量。[26]

储量

[编辑]铜的使用已有一万年的历史,但有95%的铜是在1900年后开采冶炼的[27],超过半数的铜是在近24年开采的。像很多自然资源一样,铜在地球中的总储量十分巨大(在距离地表一公里以内的地壳中约有1014吨,以现在的速度可开采五百万年)。不过,以现在的技术水平和物价,这些储量中只有一小部分在经济上有开采价值。对现有可开采储量的估计从25年到60年不等,这取决于对增长率等核心指标的假设。[28]现在也有很大一部分铜来源于回收。[27]未来铜的供求状况是个颇有争议的话题,其中涉及类似于哈伯特顶点的产量顶点。

铜价被认为是反映世界经济的指标。[29]铜价历来波动很大[30],在1999年6月创下0.60美元每磅(1.32美元每公斤)后便翻了六倍,升至2006年5月的3.75美元每磅(8.27美元每公斤),到了2007年2月又降至2.40美元每磅(5.29美元每公斤),到同年4月又反弹至3.50美元每磅(7.71美元每公斤)。[31]2009年2月,全球需求疲软和商品价格下跌使得铜价从一年前的高点回落至1.51美元每磅。[32]

方法

[编辑]

铜矿的平均含铜量仅为0.6%,商业铜矿主要是硫化物矿,特别是黄铜矿(CuFeS2),其次是辉铜矿(Cu2S)。[33]矿石粉碎后经过{{link-en|泡沫浮选|froth flotation}}或生物浸出浓缩,含铜量提高至10%到15%。[34]然后把矿石与二氧化硅一起{{link-en|闪速熔炼|flash smelting}},可把铁转化为{{link-en|矿渣|slag}}除去。这个过程利用了铁的硫化物更容易转化成氧化物,然后和二氧化硅反应生成硅酸盐矿渣漂浮在热熔物表面的特点。生成的铜锍成分为硫化亚铜,{{link-en|焙烧|Roasting (metallurgy)}}后转化成氧化亚铜:[33]

- 2 Cu2S + 3 O2 → 2 Cu2O + 2 SO2

继续加热后氧化亚铜与硫化亚铜反应转化为粗铜:

- 2 Cu2O + Cu2S → 6 Cu + 2 SO2

这种工艺只把一半的硫化物转化成氧化物,生成的氧化物再把其余的硫化物氧化后去除。所得产物经过电解精炼,阳极泥里所含的金和铂还可利用。这一步利用了铜的氧化物容易还原成金属单质的特点。先用天然气在粗铜上吹以去除大部分剩余的氧化物,然后再对产物进行电解精炼,得到纯铜。[35]

- Cu2+ + 2 e− → Cu

回收

[编辑]铜像铝一样,不管是原材料还是在产品中,都能100%回收。按体积计算,铜的回收量仅次于铁和铝,排名第三。估计已开采出的铜有80%现在仍在使用。[36]根据国际资源小组在《{{link-en|社会的金属存量|Metal Stocks in Society report}}》报告估计,全球社会人均拥有35到55公斤铜可以使用,其中发达国家人均拥有量较高(140到300公斤),而欠发达国家人均拥有量较低(30到40公斤)。[37]

铜的回收过程和开采过程基本相同,但步骤更少。高纯度的废铜在熔炉中熔化、还原、然后铸造成{{link-en|坯|billet}}和锭。低纯度的废铜通过在硫酸中电镀的方法精炼。[38]

合金

[编辑]{{see also|铜合金列表}} 铜合金种类众多,用途重要。黄铜是铜锌合金。青铜通常指铜锡合金,但也可指{{link-en|铝青铜|aluminium bronze}}等其他铜合金。在珠宝业中,铜是克拉金、克拉银等合金的重要组分之一[39],也用于克拉金的焊料,能改变合金的颜色、硬度和熔点。[40]

铜和镍的合金称为白铜,用于小面额硬币,常用作包层。5美分硬币(nickel)含75%铜,25%镍,为匀质材料。90%铜和10%镍的合金抗腐蚀性能优异,用于各种接触海水的零件部位。铜铝合金(约含7%铝)呈金色,用于装饰,令人赏心悦目。[23]有些不含铅的焊料就是锡和一小部分铜等其他金属的合金。[41]

化合物

[编辑]{{category see also|铜化合物}} 铜化合物种类繁多,其最常见的氧化数是+1和+2,分别称为亚铜(cuprous)和铜(cupric)。[42]

简单化合物

[编辑]和其他元素一样,铜能够形成二元化合物,即只有两种元素组成的化合物,主要有氧化物、硫化物和卤化物。氧化物有氧化亚铜和氧化铜,硫化物有很多种,其中硫化亚铜和硫化铜较为重要。

铜的一价卤化物有氯化亚铜、溴化亚铜和碘化亚铜,二价卤化物有氟化铜、氯化铜和溴化铜。若尝试制备碘化铜,则会得到碘化亚铜和碘单质。[42]

- 2 Cu2+ + 4 I− → 2 CuI + I2

铜的其它简单化合物有硫酸铜、硝酸铜、乙酸铜、四氟硼酸铜等,这些化合物都有蓝色调(乙酸铜蓝绿)。不溶的有氢氧化铜、氢氧化亚铜、碱式碳酸铜等。

配合物化学

[编辑]

和其他金属一样,铜和其他配体形成配合物。在水溶液中的二价铜以[Cu(H2O)6]2+离子存在,在过渡金属水合络合物中具有最大的水分子交换速率(即水分子配体结合和分离的速率)。加入氢氧化钠后形成亮蓝色的氢氧化铜沉淀。反应方程式可简单写成:

- Cu2+ + 2 OH− → Cu(OH)2

加入氨水会发生类似反应。氨水过量时沉淀溶解,生成{{link-en|氢氧化四氨合铜|Schweizer's reagent}}:

- Cu(H2O)4(OH)2 + 4 NH3 → [Cu(H2O)2(NH3)4]2+ + 2 H2O + 2 OH−

铜也可以和其他{{link-en|含氧酸根离子|Oxyanion}}形成配合物,如乙酸铜、硝酸铜和碳酸铜。硫酸铜可生成五水合物的蓝色晶体,是实验室中最常见的铜化合物,还用于杀真菌剂波尔多液。

多元醇(即含有多于一个羟基的有机化合物)一般都能与铜盐反应。例如,铜盐能用于检验还原糖。特别是本内迪克特试剂和斐林试剂在有糖存在的情况下会变色,从蓝色的二价铜变为红色的氧化亚铜。[43]{{link-en|施魏策尔试剂|Schweizer's reagent}}和其他相关的乙二胺等胺配合物能溶解纤维素。[44]氨基酸能与二价铜形成螯合物。有很多液相检验二价铜离子的方法,如亚铁氰化钾与二价铜盐生成棕色沉淀。

有机铜化学

[编辑]{{main|有机铜化合物}} 有机铜化合物是含有碳铜键的化合物。它们容易和氧气反应,生成氧化亚铜,在化学中有很多用途。这种化合物可由一价铜和格氏试剂、末端炔烃或有机锂化合物反应生成[45],特别是最后一个反应会生成吉尔曼试剂。这些试剂能和卤代烷烃发生取代反应形成偶联化合物,因此在有机合成中很重要。乙炔铜对震动高度敏感,是卡迪奥-肖德凯维奇偶联反应[46]和薗头耦合反应的中间产物。[47]有机铜化合物还能对不饱和醛酮进行亲核共轭加成[48],以及对炔烃进行亲核加成。[49]一价铜能与烯烃和一氧化碳形成多种结合较弱的配合物,特别是当有氨作为配体时。[50]

三价铜和四价铜

[编辑]三价铜通常以氧化物方式存在,例如蓝黑色固体铜(III)酸钾。[51]研究最深入的三价铜化合物是含铜(III)酸根的高温超导体。钇钡铜氧就含有二价和三价的铜。像氧离子一样,氟离子也有很强的碱性[52],能稳定金属离子的较高价态。确实有三价铜和四价铜的氟化物,如六氟合铜(III)酸钾和六氟合铜(IV)酸铯。[42]

一些含铜的蛋白质含有三价铜,与氧配体相结合。[53]{{link-en|四肽|Tetrapeptide}}中未结合质子的酰胺配体能稳定三价铜,形成紫色配合物。[54]

历史

[编辑]红铜时代

[编辑]{{main|红铜时代}} 有记载的最古老的几个文明知道自然界中存在着自然铜,其应用有至少一万年的历史。据估计,铜最早在公元前9千年的中东发现[55],在伊拉克北部出土了8700年前的铜质坠饰。[56]有证据显示在此之前人类使用的金属只有金和陨铁(但没有炼铁)。[57]据信炼铜的历史发展顺序如下:(1)自然铜的{{link-en|冷加工|cold working}}、(2)退火、(3)冶炼、(4)失蜡法铸造。在东南安那托利亚,这四种冶金方式在公元前7500年的新石器时代初期几乎同时出现。[58]不过,炼铜在世界各地独立出现,就像农业一样。公元前2800年以前的中国,公元后600年的中美洲,公元后九至十世纪的非洲都可能已经发现铜的冶炼方法。[59]{{link-en|熔模铸造|investment casting}}发现于公元前4500到4000年的东南亚。[55]碳测年确定英国柴郡的{{link-en|阿尔德利埃奇|Alderley Edge}}在公元前2280年到1890年已经有铜的开采。[60]生活在3300到3200年前的冰人奥茨出土时带有一把斧子,斧头是99.7%纯的铜,另外他的头发砷含量很高,这表明他从事过铜的冶炼。[61]铜的使用经验有助于开发其他金属为己所用,特别是炼铜使人类发明了炼铁。[61]位于现在密歇根州和威斯康辛州的{{link-en|旧红铜文明群|Old Copper Complex}}在公元前6000到3000年之间就在生产铜。[62][63]

青铜时代

[编辑]{{main|青铜时代}} 在发明炼铜之后的4000年,人类开始把铜和锡熔炼成合金,是为青铜。温查文明在公元前4500年就出现了青铜器。[64]苏美尔和古埃及的青铜器出现在公元前3000年。[65]东南欧的青铜时代在公元前3700到3300年开启,西北欧则在公元前2500年开启。后来,近东在公元前2000到1000年进入铁器时代,北欧则是公元前600年。

铜是古代就已经知道的金属之一。一般认为人类知道的第一种金属是金,其次就是铜。铜在自然界储量非常丰富,并且加工方便。铜是人类用于生产的第一种金属,最初人们使用的只是存在于自然界中的天然单质铜,用石斧把它砍下来,便可以锤打成多种器物。随着生产的发展,只是使用天然铜制造的生产工具就不敷应用了,生产的发展促使人们找到了从铜矿中取得铜的方法。

含铜的矿物比较多见,大多具有鲜艳而引人注目的颜色,例如:金黄色的黄铜矿CuFeS2,鲜绿色的孔雀石CuCO3Cu(OH)2,深蓝色的石青2CuCO3Cu(OH)2,赤铜矿Cu2O,辉铜矿Cu2S等,把这些矿石在空气中焙烧后形成氧化铜CuO,再用碳还原,就得到金属铜。反应方程式:

,另外,斑铜矿也是很常见的铜矿石。

纯铜制成的器物太软,易弯曲。人们发现把锡掺到铜里去,可以制成铜锡合金──青铜。青铜比纯铜坚硬,使人们制成的劳动工具和武器有了很大改进,人类进入了青铜时代,结束了人类历史上的新石器时代。

应用

[编辑]

- 铜的价格在10~5美元每千克(相比较银850-550美元每千克)。

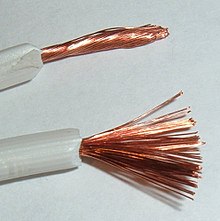

- 铜的最普遍用途在于制造电线,通常现时所用的电线都是由纯铜制成,这是因为它的导电性和导热性都仅次于银,但却比银便宜得多。而且铜很容易加工,透过熔解、铸造、压延等工序改变形状,便可制成汽车零件以及电子零件。这些经过加工的铜制品,统称为“伸铜品”。

而铜可用于制造多种合金,铜的重要合金有以下几种:

- 黄铜

黄铜是铜与锌的合金,因色黄而得名。黄铜的机械性能和耐磨性能都很好,可用于制造精密仪器、船舶的零件、枪炮的弹壳、水龙头等。黄铜敲起来声音好听,因此锣、钹、铃、号等乐器都是用黄铜制做的。 - 航海黄铜

铜与锌、锡的合金,抗海水侵蚀,可用来制作船的零件、平衡器。 - 青铜

铜与锡的合金叫青铜,因色青而得名。在古代为常用合金(如中国的青铜时代)。青铜一般具有较好的耐腐蚀性、耐磨性、铸造性和优良的机械性能,且硬度大。用于制造精密轴承、高压轴承、船舶上抗海水腐蚀的机械零件以及各种板材、管材、棒材等。青铜还有一个反常的特性——“热缩冷胀”,用来铸造塑像,冷却后膨胀,可以使眉目更清楚。 - 磷青铜

磷青铜是铜、锡与磷的合金,其中含有锡2%-8%,含有磷2-8%,其余成分余为铜。坚硬,可制弹簧。铸件可用于齿轮、蜗轮、轴承等机械部件。 - 白铜

白铜是铜与镍的合金,其色泽和银一样,银光闪闪,不易生锈。常用于制造硬币、电器、仪表和装饰品。 - 十八开金(18K金或称玫瑰金)

6/24的铜与18/24的金的合金。红黄色,硬度大,可用来制作首饰、装饰品。

铜对人体的影响

[编辑]

{{main|铜营养}} 铜的离子(铜质)对生物而言,不论是动物或植物,是必需的元素。人体缺乏铜会引起贫血,毛发异常,骨骼和动脉异常,以至脑障碍。但如过剩,会引起肝硬化、腹泻、呕吐、运动障碍和知觉神经障碍。

一般来说,牛肉、葵花籽、可可、黑椒、羊肝、螺旋藻、牡蛎等等都有丰富的铜质。[66]

正常人体内含铜100-200毫克,约50%-70%存在肌肉及骨骼,20%存在肝脏,5%-10%分布于血液。从食物吸收的铜进入肝门静脉({{lang|en|Hepatic portal vein}}),在血浆中铜与白蛋白({{lang|en|Albumin}},ALB)形成松散的结合,运送至肝脏内储存与供体内利用。肝中合成原血浆铜蓝蛋白({{lang|en|apoceruloplasmin}}),与铜牢固结合形成血浆铜蓝蛋白({{lang|en|ceruloplasmin}}),约占成人血浆铜的95%,释入血浆运送全身。

在失眠的人群中,显示有过量铜的迹象。

世界10大铜消费国之消费量

[编辑]单位:千公顷

| 国名 | 1977 | 1982 | 1987 | 1992 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 美国 | 1986.6 | 1664.2 | 1276.7 | 2057.8 |

| 日本 | 1127.1 | 1243.0 | 1276.6 | 1613.2 |

| 德国 | 894.9 | 847.8 | 970.1 | 994.8 |

| 前苏联 | 1290.0 | 1320.0 | 1270.0 | 880.0 |

| 中国大陆 | 346.0 | 398.0 | 470.0 | 590.0 |

| 法国 | 326.1 | 419.0 | 399.0 | 481.2 |

| 意大利 | 326.0 | 342.0 | 420.0 | 470.7 |

| 比利时 | 295.4 | 277.1 | 291.8 | 372.0 |

| 韩国 | 53.2 | 131.9 | 259.0 | 343.2 |

| 英国 | 512.2 | 355.4 | 327.7 | 269.4 |

| 十大国消费量 | 7157.5 | 6998.4 | 7810.9 | 8072.3 |

| 全球消费量 | 9059.9 | 9033.1 | 10413.6 | 10714.0 |

参考文献

[编辑]{{reflist|33em}}

延伸阅读

[编辑]{{Wikisource further reading}}

外部链接

[编辑]{{Elements.links|Cu|29}} {{-}} {{过渡金属|Cu}} {{过渡金属1}} {{铜化合物}} {{珠宝材料}}

{{Authority control}}

4 Category:电导体 Category:过渡金属 Category:生命化学元素 Category:膳食矿物质 Category:重金属

- ^ Magnetic susceptibility of the elements and inorganic compounds {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110303222309/http://www-d0.fnal.gov/hardware/cal/lvps_info/engineering/elementmagn.pdf |date=2011-03-03 }} in {{RubberBible86th}}

- ^ {{cite book | title = Encyclopedia of the Elements | url = https://archive.org/details/encyclopediaelem00engh | author = Enghag | year = 2004 | publisher = Wiley-VCH | isbn = 3-527-30666-8 | page=144}}

- ^ {{cite book |editor1-last=McHenry |editor1-first=Charles |title=The New Encyclopedia Britannica |date=1992 |publisher=Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc. |location=Chicago |isbn=978-0-85229-553-3 |page=612 |volume=3 |edition=15}}

- ^ {{cite web|url=https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/copper%7Cpublisher=Merriam-Webster Dictionary|title=Copper|date=2018|accessdate=22 August 2018|archive-date=2019-06-22|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190622075928/https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/copper%7Cdead-url=no}}

- ^ {{cite web |editor-last = Johnson, MD PhD |editor-first = Larry E. |title = Copper |work = Merck Manual Home Health Handbook |publisher = Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc. |date = 2008 |url = http://www.merckmanuals.com/home/disorders_of_nutrition/minerals/copper.html |accessdate = 7 April 2013 |archive-date = 2014-07-14 |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20140714205351/http://www.merckmanuals.com/home/disorders_of_nutrition/minerals/copper.html |dead-url = no }}

- ^ {{citeweb|url=http://www.copper.org/consumers/health/cu_health_uk.htm |title=Copper in human health}}

- ^ 7.0 7.1 7.2 {{cite book|author1=George L. Trigg|author2=Edmund H. Immergut|title=Encyclopedia of applied physics|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=sVQ5RAAACAAJ%7Caccessdate=2011-05-02%7Cdate=1992-11-01%7Cpublisher=VCH Publishers|isbn=978-3-527-28126-8|pages=267–272|volume=4: Combustion to Diamagnetism|archive-date=2013-05-27|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130527233937/http://books.google.com/books?id=sVQ5RAAACAAJ%7Cdead-url=no}}

- ^ {{cite book|author = Smith, William F.|author2 = Hashemi, Javad|last-author-amp = yes |title = Foundations of Materials Science and Engineering|page = 223|publisher = McGraw-Hill Professional|date= 2003|isbn = 0-07-292194-3}}

- ^ 9.0 9.1 9.2 {{cite book|author = Hammond, C. R.|title = The Elements, in Handbook of Chemistry and Physics|edition = 81st|publisher = CRC press|isbn = 0-8493-0485-7|date = 2004}}

- ^ {{cite book|author=Resistance Welding Manufacturing Alliance |title=Resistance Welding Manual|date=2003|publisher=Resistance Welding Manufacturing Alliance|isbn=0-9624382-0-0|edition=4th|pages=18–12}}

- ^ {{cite web|title=Galvanic Corrosion|url=http://www.corrosion-doctors.org/Forms-galvanic/galvanic-corrosion.htm%7Cwork=Corrosion Doctors|accessdate=2011-04-29|archive-date=2011-05-18|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110518073121/http://www.corrosion-doctors.org/Forms-galvanic/galvanic-corrosion.htm%7Cdead-url=no}}

- ^ {{Cite book|last = Chambers|first = William|last2 = Chambers|first2 = Robert|title = Chambers's Information for the People|publisher = W. & R. Chambers|date = 1884|volume = L|page = 312|edition = 5th|url = http://books.google.com/?id=eGIMAAAAYAAJ%7Cisbn = 0-665-46912-8}}

- ^ {{cite web|title=Copper.org: Education: Statue of Liberty: Reclothing the First Lady of Metals – Repair Concerns|url=http://www.copper.org/education/liberty/liberty_reclothed1.html%7Cwork=Copper.org%7Caccessdate=2011-04-11%7Carchive-date=2011-05-14%7Carchive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110514033302/http://www.copper.org/education/liberty/liberty_reclothed1.html%7Cdead-url=no}}

- ^ {{cite journal|last1=Rickett|first1=B. I.|last2=Payer|first2=J. H.|title=Composition of Copper Tarnish Products Formed in Moist Air with Trace Levels of Pollutant Gas: Hydrogen Sulfide and Sulfur Dioxide/Hydrogen Sulfide|url=https://archive.org/details/sim_journal-of-the-electrochemical-society_1995-11_142_11/page/3723%7Cjournal=Journal of the Electrochemical Society|date=1995|volume=142|issue=11|pages=3723–3728|doi=10.1149/1.2048404}}

- ^ {{cite journal|coauthors=Mitchell, S. A., Hackett, P. A.|title=Gas-phase reactions of copper atoms: formation of copper dicarbonyl, bis(acetylene)copper, and bis(ethylene)copper|journal=The Journal of Physical Chemistry|date=1991-10-01|volume=95|issue=22|pages=8719–8726|doi=10.1021/j100175a055|last=Blitz|first=M. A.}}

- ^ 《无机化学丛书》.第六卷 卤素 铜分族 锌分族. 科学出版社. 1.5 铜的化学性质.P468-469

- ^ 周为群 朱琴玉. 普通化学(第二版). 苏州大学出版社,2014.9. 第六章 重要元素及化合物. pp.205. ISBN 978-7-5672-1076-9

- ^ 《元素单质化学反应手册》P776-779

- ^ 19.0 19.1 {{cite journal |title=Nubase2003 Evaluation of Nuclear and Decay Properties |journal=Nuclear Physics A |volume=729 |page=3 |publisher=Atomic Mass Data Center |year=2003 |doi=10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2003.11.001 |author=Audi, G |bibcode=2003NuPhA.729....3A |last2=Bersillon |first2=O. |last3=Blachot |first3=J. |last4=Wapstra |first4=A.H.}}

- ^ {{cite web |url=http://www.nndc.bnl.gov/chart/reCenter.jsp?z=29&n=35 |title=Interactive Chart of Nuclides |work=National Nuclear Data Center |accessdate=2011-04-08 |archive-date=2013-08-25 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130825141152/http://www.nndc.bnl.gov/chart/reCenter.jsp?z=29&n=35 |dead-url=no }}

- ^ {{Cite journal | last = Okazawad | first = Hidehiko | last2 = Yonekura | first2 = Yoshiharu | last3 = Fujibayashi | first3 = Yasuhisa | last4 = Nishizawa | first4 = Sadahiko | last5 = Magata | first5 = Yasuhiro | last6 = Ishizu | first6 = Koichi | last7 = Tanaka | first7 = Fumiko | last8 = Tsuchida | first8 = Tatsuro | last9 = Tamaki | first9 = Nagara | last10 = Konishi | first10 = Junji | date = 1994 | title = Clinical Application and Quantitative Evaluation of Generator-Produced Copper-62-PTSM as a Brain Perfusion Tracer for PET | journal = Journal of Nuclear Medicine | volume = 35 | issue = 12 | pages = 1910–1915 | url = http://jnm.snmjournals.org/cgi/reprint/35/12/1910.pdf | pmid = 7989968 | format = PDF | access-date = 2015-09-01 | archive-date = 2020-04-05 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20200405230517/http://jnm.snmjournals.org/content/35/12/1910.full.pdf | dead-url = no }}

- ^ {{cite journal|last1=Romano|first1=Donatella|last2=Matteucci|first2=Fransesca|title=Contrasting copper evolution in ω Centauri and the Milky Way|journal=Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters|date=2007|volume=378|issue=1|pages=L59–L63|doi=10.1111/j.1745-3933.2007.00320.x|bibcode=2007MNRAS.378L..59R|arxiv = astro-ph/0703760}}

- ^ 23.0 23.1 23.2 {{cite book|author=Emsley, John|title=Nature's building blocks: an A-Z guide to the elements|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=j-Xu07p3cKwC&pg=PA123%7Caccessdate=2011-05-02%7Cdate=2003-08-11%7Cpublisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=978-0-19-850340-8|pages=121–125|archive-date=2012-11-16|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121116232149/http://books.google.com/books?id=j-Xu07p3cKwC&pg=PA123%7Cdead-url=no}}

- ^ {{cite journal|url = http://www.minsocam.org/ammin/AM66/AM66_885.pdf%7Cjournal = American Mineralogist|volume = 66|page = 885|date = 1981|title = The largest crystals|author = Rickwood, P. C.|access-date = 2015-09-01|archive-date = 2013-08-25|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20130825210420/http://www.minsocam.org/ammin/AM66/AM66_885.pdf%7Cdead-url = yes}}

- ^ {{cite web|last=Randazzo |first=Ryan |url=http://www.azcentral.com/arizonarepublic/business/articles/2011/06/19/20110619copper-new-method-fight.html |title=A new method to harvest copper |publisher=Azcentral.com |date=2011-06-19 |accessdate=2014-04-25}}

- ^ {{cite journal|url=http://www.pnas.org/content/103/5/1209.full%7Ctitle=Metal stocks and sustainability|journal=PNAS|date=2006|volume=103|issue=5|pages=1209–1214|first1=R. B.|last1=Gordon|first2=M.|last2=Bertram|first3=T. E.|last3=Graedel|doi=10.1073/pnas.0509498103|pmc=1360560|pmid=16432205|bibcode=2006PNAS..103.1209G|access-date=2015-09-02|archive-date=2015-09-24|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150924143053/http://www.pnas.org/content/103/5/1209.full%7Cdead-url=no}}

- ^ 27.0 27.1 {{cite web|url=http://www.salon.com/tech/htww/2006/03/02/peak_copper/index.html%7Ctitle=Peak copper?|publisher=Salon – How the World Works|author=Leonard, Andrew|date=2006-03-02|accessdate=2008-03-23|deadurl=yes|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20080307042349/http://www.salon.com/tech/htww/2006/03/02/peak_copper/index.html%7Carchivedate=2008-03-07}}

- ^ {{cite book|author=Brown, Lester|title=Plan B 2.0: Rescuing a Planet Under Stress and a Civilization in Trouble|publisher=New York: W.W. Norton|date=2006|page=109|isbn=0-393-32831-7}}

- ^ {{Cite news |url=http://zh.cn.nikkei.com/politicsaeconomy/commodity/41355-2020-07-21-05-00-00.html |title=“铜博士”出现“误诊”? |work=日经中文网 |date=2020-07-21 |accessdate=2020-07-21 |archive-date=2020-07-22 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200722065440/https://zh.cn.nikkei.com/politicsaeconomy/commodity/41355-2020-07-21-05-00-00.html |dead-url=no }}

- ^ {{cite journal|last=Schmitz|first=Christopher|title=The Rise of Big Business in the World, Copper Industry 1870–1930|journal=Economic History Review|date=1986|volume=39|series=2|issue=3|pages=392–410|jstor=2596347|doi=10.1111/j.1468-0289.1986.tb00411.x}}

- ^ {{cite web|url = http://metalspotprice.com/copper-trends/%7Ctitle = Copper Trends: Live Metal Spot Prices|deadurl = yes|archiveurl = https://web.archive.org/web/20120501073103/http://metalspotprice.com/copper-trends/%7Carchivedate = 2012-05-01}}

- ^ {{cite news|url = http://www.forbes.com/2009/02/04/copper-frontera-southern-markets-equity-0205_china_51.html%7Ctitle = A Bottom In Sight For Copper|author = Ackerman, R.|date = 2009-04-02|publisher = Forbes|accessdate = 2015-09-02|archive-date = 2012-10-26|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20121026112631/http://www.forbes.com/2009/02/04/copper-frontera-southern-markets-equity-0205_china_51.html%7Cdead-url = no}}

- ^ 33.0 33.1 {{Greenwood&Earnshaw2nd}}

- ^ {{cite journal|last=Watling|first=H. R.|title=The bioleaching of sulphide minerals with emphasis on copper sulphides — A review|journal=Hydrometallurgy|date=2006|volume=84|issue=1, 2|pages=81–108|url=http://infolib.hua.edu.vn/Fulltext/ChuyenDe/ChuyenDe07/CDe53/59.pdf%7Cformat=PDF%7Cdoi=10.1016/j.hydromet.2006.05.001%7Cdeadurl=yes%7Carchiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20110818131019/http://infolib.hua.edu.vn/Fulltext/ChuyenDe/ChuyenDe07/CDe53/59.pdf%7Carchivedate=2011-08-18}}

- ^ {{cite book|last=Samans|first=Carl|title=Engineering metals and their alloys|url=https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.19384%7Cdate=1949%7Cpublisher=Macmillan%7Clocation=New York|oclc=716492542}}

- ^ {{cite web|url=http://www.copperinfo.com/environment/recycling.html%7Ctitle=International Copper Association|accessdate=2015-09-02|archive-date=2012-03-05|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120305203937/http://www.copperinfo.com/environment/recycling.html%7Cdead-url=no}}

- ^ {{cite web| url=http://www.unep.org/resourcepanel/Publications/MetalStocks/tabid/56054/Default.aspx%7C title=Metal Stocks in Society: Scientific synthesis| year=2010| publisher=联合国环境署国际资源小组| deadurl=yes| archiveurl=https://archive.is/20120914112201/http://www.unep.org/resourcepanel/Publications/MetalStocks/tabid/56054/Default.aspx%7C archivedate=2012-09-14}}

- ^ {{cite web| url=http://www.copper.org/publications/newsletters/innovations/1998/06/recycle_overview.html%7C title=Overview of Recycled Copper| publisher=Copper.org| date=2010-08-25| accessdate=2011-11-08| archive-date=2017-04-30| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170430131422/https://www.copper.org/publications/newsletters/innovations/1998/06/recycle_overview.html%7C dead-url=no}}

- ^ {{cite web|url = http://www.utilisegold.com/jewellery_technology/colours/colour_alloys/%7Caccessdate = 2009-06-06|title = Gold Jewellery Alloys|publisher = World Gold Council|deadurl = yes|archiveurl = https://web.archive.org/web/20080619061619/http://www.utilisegold.com/jewellery_technology/colours/colour_alloys/%7Carchivedate = 2008-06-19}}

- ^ {{cite journal | title = A low melting point solder for 22 carat yellow gold | first1 = David M. | last1 = Jacobson | first2 = Satti P. S. | last2 = Sangha | journal = Gold Bulletin | volume = 29 | issue = 1 | pages = 3-9 | url = http://download.springer.com/static/pdf/863/art%253A10.1007%252FBF03214735.pdf?originUrl=http%3A%2F%2Flink.springer.com%2Farticle%2F10.1007%2FBF03214735&token2=exp=1441266798~acl=%2Fstatic%2Fpdf%2F863%2Fart%25253A10.1007%25252FBF03214735.pdf%3ForiginUrl%3Dhttp%253A%252F%252Flink.springer.com%252Farticle%252F10.1007%252FBF03214735*~hmac=9974e9485403d3d6018a7e19b0af7f3e73348b7f74c24232b83b7512da86d794 | date = 1996年3月 }}{{dead link|date=2018年5月 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}

- ^ {{cite web|url=http://www.balverzinn.com/downloads/Solder_Sn97Cu3.pdf%7Ctitle=Balver Zinn Solder Sn97Cu3|accessdate=2011-11-08|deadurl=yes|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20110707210148/http://www.balverzinn.com/downloads/Solder_Sn97Cu3.pdf%7Carchivedate=2011-07-07}}

- ^ 42.0 42.1 42.2 {{cite book |last1=Holleman |first1=A. F. |last2=Wiberg |first2=N. |title=Inorganic Chemistry |date=2001 |publisher=Academic Press |location=San Diego |isbn=978-0-12-352651-9}}

- ^ Ralph L. Shriner, Christine K. F. Hermann, Terence C. Morrill, David Y. Curtin, Reynold C. Fuson "The Systematic Identification of Organic Compounds" 8th edition, J. Wiley, Hoboken. ISBN 978-0-471-21503-5

- ^ Kay Saalwächter, Walther Burchard, Peter Klüfers, G. Kettenbach, and Peter Mayer, Dieter Klemm, Saran Dugarmaa "Cellulose Solutions in Water Containing Metal Complexes" Macromolecules 2000, 33, 4094–4107. {{DOI|10.1021/ma991893m}}

- ^ "Modern Organocopper Chemistry" Norbert Krause, Ed., Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2002. ISBN 978-3-527-29773-3.

- ^ {{cite journal|last1=Berná|first1=José|last2=Goldup|first2=Stephen|last3=Lee|first3=Ai-Lan|last4=Leigh|first4=David|last5=Symes|first5=Mark|last6=Teobaldi|first6=Gilberto|last7=Zerbetto|first7=Fransesco|title=Cadiot–Chodkiewicz Active Template Synthesis of Rotaxanes and Switchable Molecular Shuttles with Weak Intercomponent Interactions|journal=Angewandte Chemie|date=2008-05-26|volume=120|issue=23|pages=4464–4468|doi=10.1002/ange.200800891}}

- ^ {{cite journal|title = The Sonogashira Reaction: A Booming Methodology in Synthetic Organic Chemistry|author = Rafael Chinchilla|author2 = Carmen Nájera|last-author-amp = yes|journal = Chemical Reviews|date = 2007|volume = 107|issue = 3|pages = 874–922|doi = 10.1021/cr050992x|pmid = 17305399}}

- ^ {{cite journal |date=1986 |title=An Addition of an Ethylcopper Complex to 1-Octyne: (E)-5-Ethyl-1,4-Undecadiene |journal=Organic Syntheses |volume=64 |page=1 |url=http://www.orgsyn.org/orgsyn/pdfs/CV7P0236.pdf |format=PDF |doi=10.15227/orgsyn.064.0001 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20120619005340/http://www.orgsyn.org/orgsyn/pdfs/CV7P0236.pdf |archivedate=2012-06-19 }}

- ^ {{cite journal |last1=Kharasch |first1=M. S. |last2=Tawney |first2=P. O. |date=1941|title=Factors Determining the Course and Mechanisms of Grignard Reactions. II. The Effect of Metallic Compounds on the Reaction between Isophorone and Methylmagnesium Bromide |journal=Journal of the American Chemical Society |volume=63 |issue=9 |pages=2308–2316 |doi=10.1021/ja01854a005}}

- ^ {{cite journal|last= Imai |first= Sadako |last2= Fujisawa |first2= Kiyoshi |last3= Kobayashi |first3= Takako |last4= Shirasawa |first4= Nobuhiko |last5= Fujii |first5= Hiroshi |last6= Yoshimura |first6= Tetsuhiko |last7= Kitajima |first7= Nobumasa |last8= Moro-oka |first8= Yoshihiko |title= 63Cu NMR Study of Copper(I) Carbonyl Complexes with Various Hydrotris(pyrazolyl)borates: Correlation between 63Cu Chemical Shifts and CO Stretching Vibrations|journal= Inorg. Chem.|date= 1998| volume =37|pages=3066–3070|doi=10.1021/ic970138r|issue=12}}

- ^ {{cite book|chapter=Potassium Cuprate (III)|title=Handbook of Preparative Inorganic Chemistry|edition=2nd Ed.|editor=G. Brauer|publisher=Academic Press|year=1963|location=NY|volume=1|page=1015}}

- ^ {{cite journal|author=Schwesinger, Reinhard; Link, Reinhard; Wenzl, Peter; Kossek, Sebastian |title=Anhydrous phosphazenium fluorides as sources for extremely reactive fluoride ions in solution|doi=10.1002/chem.200500838|year=2006|journal=Chemistry – A European Journal|volume=12|issue=2|pages=438}}

- ^ {{cite journal |last1=Lewis |first1=E. A. |last2=Tolman |first2=W. B. |date=2004 |title=Reactivity of Dioxygen-Copper Systems |journal=Chemical Reviews |volume=104 |pages=1047–1076 |doi=10.1021/cr020633r |issue=2 |pmid=14871149}}

- ^ {{cite journal |last1=McDonald |first1=M. R. |last2=Fredericks |first2=F. C. |last3=Margerum |first3=D. W. |date=1997 |title=Characterization of Copper(III)-Tetrapeptide Complexes with Histidine as the Third Residue |journal=Inorganic Chemistry |volume=36 |pages=3119–3124|doi=10.1021/ic9608713|pmid=11669966 |issue=14}}

- ^ 55.0 55.1 {{cite web|url=http://www.csa.com/discoveryguides/copper/overview.php%7Ctitle=CSA – Discovery Guides, A Brief History of Copper|publisher=Csa.com|accessdate=2008-09-12|archive-date=2015-02-03|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150203154021/http://www.csa.com/discoveryguides/copper/overview.php%7Cdead-url=no}}

- ^ {{cite book|page = 56|title = Jewelrymaking through History: an Encyclopedia|publisher= Greenwood Publishing Group|date = 2007|isbn = 0-313-33507-9|author = Rayner W. Hesse}}书中未提及一手来源。

- ^ {{cite web|url=http://elements.vanderkrogt.net/element.php?sym=Cu%7Ctitle=Copper%7Cpublisher=Elements.vanderkrogt.net%7Caccessdate=2008-09-12%7Carchive-date=2010-01-23%7Carchive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100123003018/http://elements.vanderkrogt.net/element.php?sym=Cu%7Cdead-url=no}}

- ^ {{cite book|last=Renfrew|first=Colin|authorlink=Colin Renfrew, Baron Renfrew of Kaimsthorn|title=Before civilization: the radiocarbon revolution and prehistoric Europe|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=jJhHPgAACAAJ%7Caccessdate=2011-12-21%7Cdate=1990%7Cpublisher=Penguin%7Cisbn=978-0-14-013642-5%7Carchive-date=2012-11-16%7Carchive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121116222630/http://books.google.com/books?id=jJhHPgAACAAJ%7Cdead-url=no}}

- ^ {{cite news|author = Cowen, R.|url = http://www.geology.ucdavis.edu/~cowen/~GEL115/115CH3.html%7Ctitle = Essays on Geology, History, and People|chapter = Chapter 3: Fire and Metals: Copper|accessdate = 2009-07-07|archive-date = 2008-05-10|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20080510150436/http://www.geology.ucdavis.edu/~cowen/~GEL115/115CH3.html%7Cdead-url = no}}

- ^ {{cite book|author = Timberlake, S.|author2 = Prag A.J.N.W.|last-author-amp = yes|date = 2005|title = The Archaeology of Alderley Edge: Survey, excavation and experiment in an ancient mining landscape|location = Oxford|publisher = John and Erica Hedges Ltd.|page = 396 |doi=10.30861/9781841717159}}

- ^ 61.0 61.1 {{cite web|title=CSA – Discovery Guides, A Brief History of Copper|url=http://www.csa.com/discoveryguides/copper/overview.php%7Cwork=CSA Discovery Guides|accessdate=2011-04-29|archive-date=2015-02-03|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150203154021/http://www.csa.com/discoveryguides/copper/overview.php%7Cdead-url=no}}

- ^ Pleger, Thomas C. "A Brief Introduction to the Old Copper Complex of the Western Great Lakes: 4000–1000 BC", Proceedings of the Twenty-seventh Annual Meeting of the Forest History Association of Wisconsin {{Wayback|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=6NUQNQAACAAJ |date=20160102213842 }}, Oconto, Wisconsin, 5 October 2002, pp. 10–18.

- ^ Emerson, Thomas E. and McElrath, Dale L. Archaic Societies: Diversity and Complexity Across the Midcontinent {{Wayback|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=awsA08oYoskC&pg=PA709%7Cdate=20160102213842}}, SUNY Press, 2009 ISBN 978-1-4384-2701-0.

- ^ {{cite web | url = http://antiquity.ac.uk/ant/087/ant0871030.htm | title = Tainted ores and the rise of tin bronzes in Eurasia, c. 6500 years ago | first = Miljana | last = Radivojević | first2 = Thilo | last2 = Rehren | publisher = Antiquity Publications Ltd | date = December 2013 | accessdate = 2015-09-05 | archive-date = 2014-02-05 | archive-url = https://archive.is/20140205001504/http://antiquity.ac.uk/ant/087/ant0871030.htm | dead-url = no }}

- ^ {{cite book|pages = 13, 48–66|title = Encyclopaedia of the History of Technology|author = McNeil, Ian |publisher = Routledge|date = 2002|location = London ; New York|isbn = 0-203-19211-7}}

- ^ {{Cite web|url=http://webmd.cn/2018/10/foods-high-in-copper/%7Ctitle=8种高铜食物,铜食物排行榜,含铜高的食物排行榜%7Caccessdate=2018-12-11%7Cwork=WebMD%7Clanguage=zh-CN%7Carchive-date=2019-03-23%7Carchive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190323002645/http://webmd.cn/2018/10/foods-high-in-copper/%7Cdead-url=no}}