畜牧业对环境的影响

由于世界各地所采的农作方式各式各样,畜牧业对环境的影响(英语:Environmental impacts of animal agriculture)在各地也不相同。但人们发现所有农业活动都会在某种程度上对环境产生影响(参见农业对环境的影响)。畜牧业,特别是肉类生产,会产生污染、温室气体排放、生物多样性丧失、疾病以及耗用大量土地、食物和水。肉类可透过几种饲养方式方式取得,包括有机农业、自由放养、集约化饲养和自给农业。畜牧业还包括剪取羊毛、生产鸡蛋和乳制品、饲养耕作用牲畜以及水产养殖。

畜牧业被认为是导致当前生物多样性丧失危机的主要因素之一。[1][2][3][4][5]由联合国生物多样性和生态系统服务政府间科学政策平台(IPBES)发布的2019年全球生物多样性及生态系统评估中提出工业化农业和过度捕捞是导致物种灭绝的主要驱动因素,其中肉类和奶制品产业发挥有重大作用。[6][7]粮农组织 (FAO) 在2006年发布名为《畜牧业的巨大阴影:环境问题与选择方案》的报告中指出,"畜牧业是许多生态系统和地球整体的主要压力源。这个产业是全球最大温室气体 (GHG) 来源之一,也是生物多样性丧失的主要原因之一,在发达国家和发展中国家中均为水污染的主要来源。"[8]

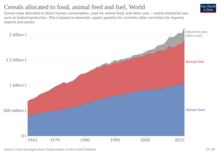

放牧占用地球无冰陆地面积的26%,而种植饲料作物又占用约3分之1的耕地,[8]或约75%的农用土地。[9][10]全球粮食系统所产生的温室气体排放占全球人为温室气体排放量的3分之1,[11][12]其中畜牧业占有近60%。[13][14]

而种植供人类消费和供动物食用的农作物之间也会发生粮食与饲料之争的情况,[15][16][17]这种"全球土地争夺"[18]也对粮食安全产生影响。[19]畜牧业,尤其是其中牛肉生产,是热带森林遭受砍伐的主要驱动力,[13]被转化的土地中,大约有80%用于饲养牛群。[20][21]而自1970年开始的亚马逊雨林砍伐,转化的土地中有91%用于养牛场。[22][23] 对畜牧业的其他担忧包括对健康的影响,这通常与环境影响有关联。[24][25][26][27]

前述影响中的部分则归因于畜牧业的非肉类,例如羊毛、蛋类和酪农业制品的生产,以及豢养用于耕作的牲畜。据估计,世界上有多达一半的农业用地仍由兽力协助耕作。 [28]

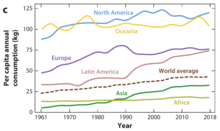

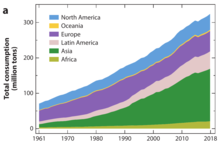

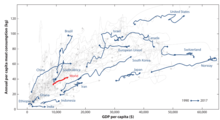

多项研究发现,目前肉类消费的增加与人口成长和个人所得(国内生产毛额(GDP)) 增加有关联。如果趋势不变,这些增长会更助长碳排放,而进一步导致生物多样性丧失。[16][29][30][31]联合国政府间气候变化专门委员会(IPCC)在其2019年特别报告摘要中和其他学者[13][16][31]均断言,为缓解和调适气候变化,世人需要转向摄取植物性饮食。[32][33]

肉类消费和生产趋势[编辑]

| 类别 | 占比 [%] |

|---|---|

| 卡路里 | 18

|

| 蛋白质 | 37

|

| 土地利用 | 83

|

| 温室气体 | 58

|

| 水污染 | 57

|

| 空气污染 | 56

|

| 淡水使用量 | 33

|

多项研究发现目前肉类消费的增加与全球人口增长和个人收入增加有关联,因此,除非人类将当前的行为发生改变,否则肉类生产和消费对环境的影响将会持续增加。[16][35][36][31]

肉类需求的变动将会影响其产量,进而改变畜牧业对环境的影响。估计全球从2000年到2050年期间的肉类消费量将会增加一倍,主要是由于世界人口不断增加,但也有部分原因是人均肉类消费量增加(增长中的大部分发生在发展中国家)[37]预计全球人口到2050年将增至90亿,而预计肉类产量将增加40%。[38]全球家禽肉类产量和消费量在近年以每年5%以上的速度成长。[37]随着人们和国家更加富裕,肉类消费通常就会增加。[39]畜牧业中不同区块的成长趋势也各不相同。例如全球人均猪肉消费量近年有所增加(几乎完全源自中国国内消费量的增加),而全球人均反刍动物肉类消费量却在下降。[37]

使用的资源[编辑]

粮食生产效率[编辑]

世界上的大豆作物中大约有85%被加工成豆粕和大豆油,几乎所有豆粕均用于动物饲料。[40]有约6%的大豆作物直接用作人类食物,多数发生在亚洲。[40]

作为人类食用而生产的作物,每100公斤中有37公斤是不适合人类直接食用的副产品。[41]许多国家将这些人类不可食用的副产品重新用作牛饲料。[42]在工业化国家,饲养供人类消费的牲畜约占农业总产值的40%。[8]而肉类生产效率因特定生产系统以及饲料类型而有差异。生产1公斤牛肉大约需要0.9至7.9公斤谷物,生产1公斤猪肉大约需要0.1至4.3公斤谷物,生产1公斤鸡肉大约需要0至3.5公斤谷物。[43][44]

然而粮农组织(FAO)估计,大约有三分之二饲养牲畜用的牧场土地无法转化为农田。[43][44]

为数不少的大型公司在拉丁美洲和亚洲的不同发展中国家取得土地,用以大规模种植饲料用作物(主要是玉米和大豆)。这种做法把此类国家可用于种植适合人类食用农作物的土地数量减少,导致当地居民面临粮食安全方面的风险。[45]

根据一项在中国江苏省进行的研究,收入较高的人往往比收入较低,与家庭人口较多的人消耗更多的食物。居住于此类地区从事动物饲料生产的人,不太可能不食用由当地生产的农作物饲养的动物。缺乏种植供人消费作物的土地,加上需要养活更多的家庭成员,只会加剧这些人的粮食不安全。[46]

根据粮农组织的资料,农作残余物和副产品占全球饲养牲畜摄取干物质总量的24%。[43][44]于2018年所做的一项研究,发现"目前于荷兰的饲料业所使用的原料,有70%来自食品加工业。"[47]于美国,以谷类废弃物转化为饲料的例子包括用酒糟。美国于2009年-2010年财务年度,用作牲畜饲料的干酒糟估计为2,550万吨。[48]可用于粗饲料的例子包括大麦和小麦的秸秆(特别是用于大型反刍种畜的维持饲料(maintenance diet))、[49][50][51]以及玉米秸秆。[52][53]

土地利用[编辑]

| 食物种类 | 土地面积 (每年生产100克蛋白质所需平方米) |

|---|---|

| 羊肉 | 185

|

| 牛肉 | 164

|

| 起司 | 41

|

| 猪肉 | 11

|

| 禽肉 | 7.1

|

| 蛋类 | 5.7

|

| 水产养殖 | 3.7

|

| 豆类 | 3.5

|

| 豌豆 | 3.4

|

| 豆腐 | 2.2

|

永久草地和牧场,无论是否用于放牧,占据地表无冰陆地面积的26%。[43][44]种植饲料作物大约使用三分之一的耕地。[43][44]美国有超过三分之一的土地用于牧场,使其成为美国本土最大单一土地利用者。<[55]

许多国家将牲畜饲养于大部分不能用于种植人类食用作物的土地上,全球耕地[56]面积仅为农业用地[57]的三分之一。

采用自由放养方式,特别是在饲养肉牛,也是导致热带森林遭到砍伐的原因之一,因为此方式需要用到大量土地。[13]畜牧业是导致亚马逊雨林遭受砍伐的主要驱动力(参见亚马逊雨林砍伐),由此取得的土地中约80%用于养牛。[58][59]而自1970年以来,当地91%的森林砍伐所得土地被用于养牛。[22][23]研究认为转向无肉饮食可为养活不断增长的人口提供安全的选择,而无需进一步砍伐森林,且在不同的产量情景下皆适用。[60]根据粮农组织的资料,在旱地放牧牲畜"可移除植被,包括干燥和易燃的植物,并激活储存于土壤中的生物质,提高肥力。畜牧业是创造和维持特定栖息地和绿色基础设施、为其他物种提供资源和传播种子的关键因素。"[61]

用水[编辑]

全球用于农业目的的水量超过全部工业目的用水量。[62]全球约80%的水资源用于农业生态系。在发达国家,高达总用水量的60%用于灌溉,在发展中国家,比例可达90%,具体取决于当地的经济状况和气候。根据到2050年粮食产量的增长预测,需要增加53%用水量才能满足世界人口对肉类和农业生产的需求。[62]

美国抽取淡水用量中,灌溉约占37%,而抽取地下水约占全国灌溉用水的42%。[63]用于生产饲料和草料的灌溉用水估计约占美国抽取淡水用量的9%。[64]在某些地区,地下水枯竭会产生永续性问题(譬如地面沉降和/或海水倒灌)。[65]玉米的特点是其约占美国牲畜和家禽饲料的91.8%(2010年)。[66]:table 1–75美国约14%的玉米种植土地使用灌溉,由此生产的玉米约占美国的17%,使用的灌溉用水占全国的13%,[67][68]但只有约40%的美国玉米用于饲养本国的牲畜和家禽。[66]:table 1–38地下水枯竭中一个特别重要的案例发生在北美大平原之下的奥加拉拉蓄水层,含水层位于8个州的部分地区,占地约174,000平方英里,由其抽取用于灌溉的淡水占全美的30%。[69]由于含水层会有枯竭的一天,长远来看,一些透过此地抽水灌溉以生产牲畜饲料,在水文上属于不可持续。在北美生产牲畜饲料多数依靠雨养农业,此法无耗尽水源的问题。

一份发表于2005年的报告声称美国抽取地表水和地下水以供灌溉作物与饲养牲畜的比例约为60:1。[63]实际上美国西部使用的水中,用于灌溉种植养牛用的作物几乎占3分之1。[70]这种过度使用河水的行为危及生态系统和社区,在干旱时期甚至导致许多鱼类濒临灭绝。[71]

于2019年进行的一项研究,重点放在中国用水与畜牧业之间的联系。[72]研究结果显示水资源主要用于畜牧业,于最高用量业别中排序,畜牧业排名第一,接下来是农业、肉类屠宰和加工、渔业和其他食品,合计消耗超过24,000亿立方米的水,大约相当于用水总量的40%。[72]表示中国有三分之一以上的水是用于食品及相关加工,其中大部分用于畜牧业。

| 食品种类 | 升 每千卡路里 |

升 每克蛋白质 |

升 每公斤产量 |

升 每克脂肪 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 制糖作物 | 0.69 | 0.0 | 197 | 0.0 |

| 蔬菜 | 1.34 | 26 | 322 | 154 |

| 淀粉类根类 | 0.47 | 31 | 387 | 226 |

| 水果 | 2.09 | 180 | 962 | 348 |

| 谷物 | 0.51 | 21 | 1644 | 112 |

| 榨油种籽 | 0.81 | 16 | 2364 | 11 |

| 豆类 | 1.19 | 19 | 4055 | 180 |

| 坚果 | 3.63 | 139 | 9063 | 47 |

| 乳类 | 1.82 | 31 | 1020 | 33 |

| 蛋类 | 2.29 | 29 | 3265 | 33 |

| 鸡肉 | 3.00 | 34 | 4325 | 43 |

| 奶油 | 0.72 | 0.0 | 5553 | 6.4 |

| 猪肉 | 2.15 | 57 | 5988 | 23 |

| 羊肉 | 4.25 | 63 | 8763 | 54 |

| 牛肉 | 10.19 | 112 | 15415 | 153 |

水污染[编辑]

因动物排泄物而造成的水污染是发达国家和发展中国家的普遍问题。[8]美国、加拿大、印度、希腊、瑞士和其他几个国家都因动物粪便造成的水污染,而发生严重的环境退化。[74]:Table I-1这种问题在集约动物饲养作业(CAFO)存在的附近更引起重大关注。美国对于颁发CAFO许可时会要求业者根据《清洁水法案》备有适当的粪便养分、污染物、污水等管理计划。[75]截至2008年,美国约有19,000家CAFO。[76]美国环境保护局(EPA)在2014财政年度为不同违规行为采取过26次执法行动。[77]美国畜牧业的环境绩效与其他几个产业并列进行比较。 EPA公布有32个产业的5年期和1年期的执法检查命令比率,为衡量不遵守环境法规(主要是《清洁水法案》和《清洁空气法案》)的措施。

有效使用肥料对于增加动物饲料生产很重要。[78]但如果过量使用,肥料会在降雨后透过地表径流进入水体,造成优氧化。[79]水体中的氮和磷增加后会导致藻类快速生长(称为藻华)。藻类大量繁殖后会导致水中氧气和营养物质减少,最终造成其他水中物种死亡。这种生态危害不仅对受影响水体中的动物产生影响,也对人类用水产生影响。[78]

为处理动物粪便和其他污染物,CAFO经常透过喷洒系统将粪浆(可能遭到细菌污染)喷洒到空旷的田地上。这些有害物质经常会受地表径流携带进入溪流、池塘、湖泊和其他水体,造成污染问题。此过程也会导致饮用水储备受到污染,伤害环境与和当地居民。[80]

空气污染[编辑]

| Food Types | 每生产100克蛋白质产生的二氧化硫(克) |

|---|---|

| 牛肉 | 343.6

|

| 起司 | 165.5

|

| 猪肉 | 142.7

|

| 羊肉 | 139.0

|

| 水产养殖 | 133.1

|

| 禽肉 | 102.4

|

| 养殖鱼类 | 65.9

|

| 蛋类 | 53.7

|

| 豆类 | 22.6

|

| 豌豆 | 8.5

|

| 豆腐 | 6.7

|

畜牧业是产生温室气体排放和大气中其他悬浮微粒污染的主要原因之一。这类生产链会产生大量副产品,包含脂多糖(内毒素)、硫化氢、氨和悬浮微粒,它们与上述甲烷和二氧化碳一起释放。[81][82]此外,温室气体排放会增加与哮喘、支气管炎和慢性阻塞性肺病等呼吸系统疾病,与因细菌感染而罹患肺炎的几率增加有关联。[83]

此外,接触PM10(直径10微米的颗粒物)有机会产生影响上呼吸道和近端呼吸道的疾病。 [84]农民并不是唯一接触这些有害副产品的人。事实上,居住在CAFO场所附近的人都会受到此类呼吸系统健康的影响。[85]集约养猪场会从圈舍、粪便贮存坑和施用粪肥的土壤中释放空气污染物。这类空气污染物会引起急性身体症状,例如呼吸道疾病、喘鸣、呼吸急促以及对眼睛和鼻的刺激。[86][87][88]接触空气中的动物性微粒,例如猪尘,会导致大量炎症细胞涌入气道。[89]

气候变化会产生相关的压力,对人类健康有负面影响。空气污染和气温升高是人类面临的两大健康风险,所有地区、社会经济群体、性别和年龄组均受到影响。每年约有700万人因空气污染的原因致死。受到污染的空气会渗透到肺组织并损害肺部,而加剧呼吸系统疾病。[90]

虽然有上述所列的多种环境后果,美国地方政府因此产业有强大的经济产值,而倾向于支持此类行业,也因为有这种保护性立法,此行业不易受到规范而将环境影响降低。 [91]

于气候变化[编辑]

能源耗用[编辑]

美国农业部的研究数据显示饲养食用牲畜和家禽用到全国0.9%的能源。能源来自化石燃料、核能、水电、生物质能、地热能、太阳能(不包含光合作用及晒干草料的太阳能)和风能。 农业生产中的能源使用包括购买投入物中的隐含能源。 [92]畜牧业在能源使用中有个重点是动物本身的能源消耗。饲料转化率( FCR)是动物将饲料转化为肉的能力。FCR的计算方法是把饲料中的能量、蛋白质或质量输入,除以动物肉的产出。较低的FCR表示每单位的肉类产出需要较少的饲料量,此类动物产生的温室气体排放量较少。鸡和猪的FCR与反刍动物相比,通常较低。[93]

畜牧业的集约化和其他变化也对肉类生产的能源使用、排放和其他环境影响方面产生影响。例如2007年当年生产每单位牛肉的化石燃料使用量与1977年比较,通常减少8.6%,温室气体排放量减少16%,水的使用量减少12%,土地使用量减少33%。[94]

粪便作为再生能源也具环境效益,在沼气池系统中产生用于加热和/或发电的沼气。粪便沼气营运可见于亚洲、欧洲、[95][96]北美洲及其他地方。[97]相对于美国能源价值而言,这种系统成本相当高,可能会阻碍更广泛的采用。其他因素,例如气味控制和碳信用,可能会提高效益成本比。[98]粪便可与厌氧消化池中的其他有机废弃物混合,产生规模经济。消化后的废弃物比未经处理的有机废弃物在稠度上更均匀,并且可含有更高比例的养分,这些养分更容易被植物利用,而增强作为肥料的效用。[99]此可促使肉类生产的资源发挥循环作用,但由于环境和食品安全问题,通常很难实现。

温室气体排放[编辑]

牛、羊和其他反刍动物透过肠道发酵消化食物,其嗝气是土地利用、土地利用改变与林业而产生甲烷排放的主要来源,加上这些动物粪便产生的甲烷和一氧化二氮,使得牲畜成为农业活动中主要的温室气体排放来源。[100]

于2022年发布的IPCC第六次评估报告指出:"多摄取植物蛋白,减少摄取肉类和乳制品的饮食方式与较低的温室气体排放有关。[...]在适当情况下,转向植物蛋白比例较高、适度摄取动物性食品和减少饱和脂肪的摄取量将会导致温室气体排放量大幅减少。好处还包括减少占用土地和营养逸入周围环境,同时提供健康益处,并降低与饮食相关的非传染性疾病所造成的死亡。"[101]

根据一篇于2022年发表的研究报告,迅速淘汰畜牧业可在30年内减少一半的温室气体排放量,而实现《巴黎协定》将全球变暖控制在不超过2°C目标。[102]

全球粮食系统所排放的温室气体,占全球人为排放量的三分之一,[103][104]其中畜牧业占近60%。[13][105]

缓解方案[编辑]

根据《自然》杂志在2018年发表的一项研究报告,大幅减少肉类消费对于缓解气候变化是"势在必行",尤其是在21世纪中叶全球人口将增加23亿时。[106]同行评审医学期刊《刺胳针》在2019年刊载的一份报告,建议把全球肉类消费量减少50%以缓解气候变化。 [107]

IPCC在2019年8月8日发布IPCC气候变化与土地特别报告,称转向植物性饮食会有助于减缓和适应气候变化。[108]

全球15,364名科学家在2017年11月签署一份"世界科学家对人类的警告",呼吁大幅减少人均肉类消费量。[109]

除减少畜产品的消费之外,还可以透过改变农法来减少排放。一份研究报告提出改变目前饲料组合、生产区域和知情的土地复育可让温室气体排放量每年减少34-85% (612至1,506百万吨二氧化碳当量),而不会增加成本或需要改变饮食。[110]

减少反刍动物肠道发酵产生甲烷而排放的缓解方案,包含利用其粪便中的生物燃气、[111]基因挑选、[112][113]免疫接种、驱除瘤胃原虫、增强产乙酸菌替代产甲烷菌的作用、[114]提供反刍动物包含甲烷营养菌的饲料、[115][116]调整饲料配方以及采用放牧的方式等。[115][116]为减少农业一氧化二氮排放的主要缓解策略是避免过度施用氮肥,和采用适当的牲畜粪肥管理。[117][118]缓解畜牧业二氧化碳排放的策略包括采用更有效的生产方式来减少砍伐森林的压力(例如在拉丁美洲),减少使用化石燃料,以及增加土壤的碳捕集能力。[119]

也可透过肉类消费/生产而增加收费的措施,然后将这类资金用于相关研究和开发,以"缓解低收入者的社会问题"。肉类和牲畜是当代社会经济体系的重要组成成分,估计当前畜牧业价值链已雇用超过13亿人。[16]

对生态系统的影响[编辑]

土壤[编辑]

放牧对牧场健康可产生积极或是消极影响,由管理品质决定,[120]放牧对不同的土壤[121]和不同的植物群落有不同的影响。[122]放牧有时会减少草原生态系统的生物多样性,有时会增加生物多样性。[123][124]养牛场可利用适合放牧来帮助保护和改善自然环境。[125]轻度放牧的草原往往会比过度放牧或不放牧的草原具有更高的生物多样性。[126]

过度放牧会持续消耗土壤中必要的养分,将土壤品质降低。[127]美国内政部土地管理局(BLM)迄2002年底已对7,437个放牧区(占放牧区的35%,或放牧区内土地面积的36%)做过健康状况评估,发现其中有16%因现有的放牧方式或使用程度,而未能达到牧场健康标准。[128]因过度放牧而发生的土壤侵蚀作用是世界许多干旱地区的重要问题。[8]而在美国农地中,因放牧而产生的土壤侵蚀要远少于因种植农作物而发生的。在美国自然资源保护局清点过的牧场土地,其中的99.4%,有95.1%的板状侵蚀和细沟侵蚀维持在土壤流失容忍范围内,风蚀造成的流失则完全在容忍范围内。[129]

放牧会影响土壤中碳截存和氮固定。这种固存有助于减轻温室气体排放的影响,在某些情况下,还可以透过影响养分循环来提高生态系统生产力。[130]于2017年发表的一项科学文献统合分析,估计放牧管理带来的全球土壤碳固存总量为每年0.3-0.8吉吨(Gt,十亿吨)二氧化碳当量,相当于全球牲畜总排放量的4-11%,但"将其扩张或强化,作为固存更多碳的方法,将会导致甲烷、一氧化二氮和因土地利用改变所引起的二氧化碳排放量大幅增加"[131]

由Paul Hawken与Amanda Joy Ravenhill两人创立的气候变化缓解计划Project Drawdown估计,于2020年至2050年期间,改善放牧管理的总碳封存潜力有13.72 - 20.92吉吨吨二氧化碳当量,相当于每年封存0.46-0.70吉吨。[132]一篇于2022年发表的同行评审论文估计,改善放牧管理的碳封存潜力为每年在0.15-0.70吉吨左右。[133]于2021年发表的一篇同行评审论文提出稀疏放牧的天然草原封存的碳占世界草原累积碳汇总量的80%,而密集放牧的草原(managed glasslands)在过去十年中一直是温室气体净排放源。[134]另一篇同行审查论文提出如果目前的牧场恢复到以前的状态,如野生草原、灌木丛和没有牲畜的疏林草原,预计可再储存15.2-59.9吉吨额外的碳。[135]一项研究,把一些有放牧和未经放牧的美国原始草地做比较,显示经放牧后,其有机土壤碳含量略低,但有较高的土壤氮含量。[136]相较之下,在怀俄明州的高原草原研究站发现,经放牧后的草地与牲畜不得进入的草原相比,其表层30厘米的土壤中有更多的有机碳和更多的氮。[137]同样的,在皮埃蒙特地区于曾遭受侵蚀的土壤上种植草类,在放牧管理良好的牧场和未经放牧的地方相比,有较高的碳和氮封存率。[138]

一篇加拿大发表的审查报告强调牲畜粪肥管理排放的甲烷和一氧化二氮占农业室温气体排放量的17%,而施用粪便后的土壤,其排放的一氧化二氮占总排放量的50%。[139]

如果能妥善管理粪便,可带来环境效益。放牧动物在牧场上排放的粪便可有效保持土壤肥力。从谷仓和集中饲养场收集动物粪便,经堆肥后,有许多养分可在种植作物时循环利用。在许多牲畜密度高地区附近的农地,粪肥基本上可取代合成肥料的使用。 在2006年,美国约有1,580万英亩的农田使用粪便作为肥料。[140]粪便也撒在牧草生长的土地上。[68]

此外,北美洲(和其他地方)有时会利用小型反刍动物于田间食用并清除人类不可食用的各种农作物残留物。小型反刍动物可用来控制牧场上的特定入侵或有害杂草(如斑点矢车菊、tansy ragwort、叶状大戟、黄星蓟、tall larkspur等)。[141]小型反刍动物也可用于种植园中的植被管理和清除小型通道上的灌木丛。其他反刍动物,如不丹的Nublang牛被用来控制一种称为Yushania microphylla的竹子,这种竹子往往会排挤本地植物物种。 [142]此类做法可作为除草剂的替代品。 [143]

生物多样性[编辑]

放牧(尤其是过度放牧)会对某些野生动物物种产生不利影响(例如把栖息地和食物供应改变)。对肉类需求不断增长,会导致森林砍伐和栖息地受到破坏,造成生物多样性的严重丧失;例如原本物种丰富的栖息地(如亚马逊地区),被转变为肉类生产基地。

非营利的世界资源研究所 (WRI) 的网站提到"全球有30%的森林遭到清除,另有20%已经退化。所余大部分已呈支离破碎状态,只剩下约15%为完好无损。"[146]WRI还指出,世界各地"估计有15亿公顷(37亿英亩)曾是有高产力的农田和牧场(几乎与俄罗斯的面积相当)正在退化中。把这些土地的生产力恢复,可改善粮食供应、水安全和应对气候变化的能力。"[147]IPBES发表的2019年全球生物多样性及生态系统评估报告同样认为肉类产业在生物多样性丧失方面具有重要作用。[148][149]全球大约有25%到近40%的土地为畜牧业使用。[148][150]

两个非营利组织 - 世界动物保护协会与生物多样性中心于2022年发表的的报告提出,根据2018年的数据,光在美国每年就有约2.35亿磅(或117,500吨)的农药于动物饲料作物生产中使用,特别是嘉磷塞和草脱净两种。报告强调100,000磅嘉磷塞有可能伤害或杀死美国《1973年濒危物种法案》中列出的约93%的物种。而有35个国家禁用草脱净,这种农药可伤害或杀死至少1,000种所列物种。这两个组织都主张消费者减少动物产品的消费,而转向植物性饮食,以减少集约化农业的增长,并保护濒临灭绝的野生动物物种。[151]

多项研究发现,在北美的放牧有时对加拿大马鹿、[152]黑尾土拨鼠、[153]艾草松鸡[154]和骡鹿栖息地有益。[155][156]对美国123个国家野生动物保护区的管理人员进行的调查,显示有86种野生动物受到正面,和82种受到负面的影响。[157]所采用的放牧系统类型(例如轮作、移地放牧、短期密集放牧)对于达成特定野生动物保护通常很重要。[158]

生物学家Rodolfo Dirzo、Gerardo Ceballos和保罗·拉尔夫·埃利希在同行评审科学期刊皇家学会哲学汇刊 B发表的一篇评论文章中写道,减少肉类消费"不仅可转化为消耗更少的热量,还可以创造更大的生物多样性空间。"他们坚信,"需要遏制工业化肉类生产在全球具有的垄断地位",同时尊重各地原住民的文化传统,肉类是他们重要的蛋白质来源。 [159]

水生生态系统[编辑]

| 食物种类 | 每100克蛋白质可产生的磷酸盐(克) |

|---|---|

| 牛肉 | 301.4

|

| 养殖鱼类 | 235.1

|

| 水产养殖 | 227.2

|

| 起司 | 98.4

|

| 羊肉 | 97.1

|

| 猪肉 | 76.4

|

| 禽肉 | 48.7

|

| 蛋类 | 21.8

|

| 豆类 | 14.1

|

| 豌豆 | 7.5

|

| 豆腐 | 6.2

|

全球农业活动是造成环境退化的主要原因之一。畜牧业活动覆盖83% 的农业用地(但所产仅占全球卡路里摄入量的18%),直接食用动物产品以及过度消费正导致栖息地改变、生物多样性丧失、气候变化、污染和营养级间的变化。[160]这些压力足以导致任何栖息地的生物多样性丧失,但淡水生态系统比其他生态系统更为敏感,却受到更少的保护,而遭受非常巨大的影响。[160]

美国西部的许多河流和河岸缓冲带栖息地都受到牲畜放牧的负面影响。导致磷酸盐和硝酸盐增加、水中溶氧减少、温度升高、水体混浊和优养化,以及物种多样性减少。[161][162]保护河岸的牲畜管理措施包括盐和矿产物质处置、季节性限制进入、使用替代水源、提供"硬化材料"所造渡河设施、驱使牲畜远离和安装围栏。 [163][164]一项在1997年针对美国东部所做的研究,发现养猪场排放的粪便会导致水体(包括密西西比河和大西洋)的大规模优氧化化。[165]有证据显示美国养猪业的环境管理从那时起开始获得改善。[166]

于2017年在阿根廷中央省分区东部进行的一项研究,发现淡水溪流中存在大量金属污染物(铬、铜、砷和铅),水生生物群受到破坏。[167]淡水系统中的铬含量超过水生生物生存建议标准的181.5倍,而铅含量超过41.6倍,铜含量超过57.5倍,砷含量超过12.9倍。研究结果显示由于农业径流、农药施用以及管理径流的措施不力,而导致污染物累积过多。[167]

畜牧业导致气候变化,随着碳排放量增加,大气中的二氧化碳与海水之间发生化学反应而导致海洋酸化。[168]此过程也称为无机碳在海水中溶解。[169]导致海中碳酸盐沉积生物难以产生保护壳,且导致海草大量繁殖。[170]海洋生物减少会产生不利影响,除会减少食物供应外,并会降低海岸受保护,免遭风暴破坏的功能。[171]

产生抗生素抗药性的影响[编辑]

本节摘自畜牧业使用抗生素的问题。

对于家禽家畜施用抗生素的时机包括发病后治疗,发现少数感染而对群体施用(疫情爆发前预防治疗,[172])以及预防性施用(预防医学)。抗生素是治疗动物和人类疾病、维护健康和福祉以及支持食品安全的重要工具。[173]但如果任意使用,可能会产生抗生素抗药性,最终影响到人类、动物以及环境的健康。[174][175][176][177]

各国间使用抗生素的情况有巨大差异,例如一些北欧国家使用抗生素来治疗动物的数量远少于用来治疗人类的,[178]全球的抗微生物剂的耗用中,有73%使用在饲养的牲畜身上。[179]此外,有项在2015年发表的研究报告估计,在2010年到2030年间,全球农业抗生素的使用量将增加67%,主要发生在金砖四国。[180]

抗生素使用量增加会导致产生抗药性的结果,对于未来的人类和动物有严重的威胁,是个令人担忧的问题,环境中有大量具抗药性的细菌会增加不易治愈的病例数量。[181]细菌性疾病是导致死亡的主要原因,缺乏有效抗生素的结果将对现代人类医学和兽医学发生颠覆性的影响。[181][182][183]现在全球正在导入农场动物使用抗生素的相关立法和其他限制措施。[184][185][186]世界卫生组织(WHO)在2017年强烈建议业者减少动物相关食品业中使用抗生素。[187]

欧盟从2006年起禁止使用促进生长的抗生素。[188]美国规定从2017年1月1日起,将在动物饲料和饮水中添加亚治疗剂量的人类医学重要抗生素[189],以促进生长和提高饲料效率为非法行为。[190][191]

肉类生产和消费的替代品[编辑]

一项研究显示新型食品,如在开发中的[192]细胞农业产品(如培植肉和培植奶制品)、藻类养殖以及既有的微生物食品加工和食用昆虫,均有减少环境影响的潜力,[16][193][194][195]有项研究称减少影响程度可达80%。[196][197][198]替代品不仅可供人类消费,也可用作宠物食品和其他动物饲料。

减少摄取肉类与健康[编辑]

饮食中用多种食材可替代肉类,例如真菌[199][200][201]或特殊的"素肉"。

然而不恰当的大幅减少肉类摄入,特别是对于"低收入国家"的儿童、青少年以及孕妇/哺乳期妇女等群体,会导致营养不足的后果。一篇综述提出在减少人们摄入肉类的同时,应增加蛋白质和微量营养素的替代来源,以避免缺乏均衡饮食中具有的如铁和锌等元素。[16]肉类以含有维生素B12、[202]胶原蛋白[203]和肌酸而著称。[204]这可透过摄取特定的食物来替代,例如富含铁的豆类和各种富含蛋白质的食物,[205]例如小扁豆、植物性粉状蛋白质[206],和/或营养补充品。[194][207][208]研究发现植物性饮食中的微量元素(如ω-3脂肪酸、四烯甲萘醌(维他命K2)、胆钙化醇(维生素D3)、碘、镁和钙)通常会低于奶制品和鱼和/或特定的其他食物。[209][210]

研究评论发现摄取植物性饮食为主与摄取肉制品的人相比,在健康和寿命[211]或是死亡率均有较佳的表现。[16][212][213][214]

减肉策略[编辑]

透过(大规模)教育和建立体认是促进更具可持续性消费方式的重要战略。荷兰哈伦市在2022年宣布将从2024年开始,禁止于公共场所展示工业化养殖肉类的广告。[215]

其他的政策性干预可能会加速转变,例如包括"设限或是财政机制,例如征收肉类税"。[16]在财政机制的情况,可采用把外部性成本列入计算。 [216]在限制的情况,可采用个人碳权配额的方式。[217][218]

与此类战略相关的是以标准化方式评估食品对环境的影响(如同超市对超过57,000种食品的数据收集类似),也可用于告知消费者或制定政策,让消费者更加了解动物产品对环境的影响(或要求他们将此列入考虑)。[219][220]

一项综述在结论时说,"在100亿人的规模,即使低度和适度的肉类消费也符合气候目标和更广阔的永续发展"。[16]

欧盟执行委员会的科学建议机制经审查所有的证据后,于2023年6月发布随附政策建议,提倡采取永续食品消费方式与减少肉类摄取。报告中提出有证据支持对定价(包括"肉类税、根据环境影响程度对产品定价,以及对健康和永续性替代品降低税收")、可用性和可见性、食品成分、标签和社会环境的政策予以干预。[221]他们并表示:

人们不仅透过理性反思来选择食物,还基于许多其他因素:食物可得性、习惯和惯例、情绪和冲动反应、以及他们的财务和社会状况。因此我们应考虑如何减轻消费者的负担,让永续、健康的食品成为简单且负担得起的选择。

养猪业[编辑]

本节摘自养猪业对环境的影响。

养猪业对环境的影响主要是由于粪便和废弃物向周围社区扩散,有毒悬浮微粒污染到空气和水。[222]养猪场的废弃物可能携有病原体、细菌(通常具有抗生素抗药性)和重金属。[31]猪粪也会透过渗漏以及在邻近土地喷洒粪浆而造成地下水污染。

喷洒粪浆和随水漂流的猪粪,其内容物已被证明会引起黏膜刺激、[223]呼吸系统疾病、[224]压力增加、[225]生活品质下降[226]和血压升高。[227]养猪场造成的环境恶化带来环境不公义问题,因为社区没有从养猪场中获得任何利益,反而遭受污染和健康问题等负面影响。[228]FAO的动物畜养与健康部(Animal Production and Health Division)表示,"饲养生猪对环境的主要直接性影响与猪只排放的粪便有关联"。[229]

参见[编辑]

参考文献[编辑]

- ^ Morell, Virginia. Meat-eaters may speed worldwide species extinction, study warns. Science. 2015 [2023-12-11]. doi:10.1126/science.aad1607. (原始内容存档于2016-12-20).

- ^ Machovina, B.; Feeley, K. J.; Ripple, W. J. Biodiversity conservation: The key is reducing meat consumption. Science of the Total Environment. 2015, 536: 419–431. Bibcode:2015ScTEn.536..419M. PMID 26231772. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.07.022.

- ^ Williams, Mark; Zalasiewicz, Jan; Haff, P. K.; Schwägerl, Christian; Barnosky, Anthony D.; Ellis, Erle C. The Anthropocene Biosphere. The Anthropocene Review. 2015, 2 (3): 196–219. S2CID 7771527. doi:10.1177/2053019615591020.

- ^ Smithers, Rebecca. Vast animal-feed crops to satisfy our meat needs are destroying planet. The Guardian. 2017-10-05 [2017-11-03]. (原始内容存档于2018-03-03).

- ^ Woodyatt, Amy. Human activity threatens billions of years of evolutionary history, researchers warn. CNN. 2020-05-26 [2020-05-27]. (原始内容存档于2020-05-26).

- ^ McGrath, Matt. Humans 'threaten 1m species with extinction'. BBC. 2019-05-06 [2019-07-03]. (原始内容存档于2019-06-30).

Pushing all this forward, though, are increased demands for food from a growing global population and specifically our growing appetite for meat and fish.

- ^ Watts, Jonathan. Human society under urgent threat from loss of Earth's natural life. The Guardian. 2019-05-06 [2019-07-03]. (原始内容存档于2019-06-14).

Agriculture and fishing are the primary causes of the deterioration. Food production has increased dramatically since the 1970s, which has helped feed a growing global population and generated jobs and economic growth. But this has come at a high cost. The meat industry has a particularly heavy impact. Grazing areas for cattle account for about 25% of the world’s ice-free land and more than 18% of global greenhouse gas emissions.

- ^ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Steinfeld, Henning; Gerber, Pierre; Wassenaar, Tom; Castel, Vincent; Rosales, Mauricio; de Haan, Cees, Livestock's Long Shadow: Environmental Issues and Options (PDF), Rome: FAO, 2006 [2023-12-11], (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2019-12-10)

- ^ If the world adopted a plant-based diet we would reduce global agricultural land use from 4 to 1 billion hectares. Our World in Data. [2022-05-27]. (原始内容存档于2023-09-24).

- ^ 20 meat and dairy firms emit more greenhouse gas than Germany, Britain or France. The Guardian. 2021-09-07 [2022-05-27]. (原始内容存档于2023-09-13) (英语).

- ^ FAO – News Article: Food systems account for more than one third of global greenhouse gas emissions. www.fao.org. [2021-04-22]. (原始内容存档于2023-09-30) (英语).

- ^ Crippa, M.; Solazzo, E.; Guizzardi, D.; Monforti-Ferrario, F.; Tubiello, F. N.; Leip, A. Food systems are responsible for a third of global anthropogenic GHG emissions. Nature Food. March 2021, 2 (3): 198–209. ISSN 2662-1355. doi:10.1038/s43016-021-00225-9

(英语).

(英语).

- ^ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 How much does eating meat affect nations' greenhouse gas emissions?. Science News. 2022-05-05 [2022-05-27]. (原始内容存档于2023-07-28).

- ^ Xu, Xiaoming; Sharma, Prateek; Shu, Shijie; Lin, Tzu-Shun; Ciais, Philippe; Tubiello, Francesco N.; Smith, Pete; Campbell, Nelson; Jain, Atul K. Global greenhouse gas emissions from animal-based foods are twice those of plant-based foods. Nature Food. September 2021, 2 (9): 724–732. ISSN 2662-1355. S2CID 240562878. doi:10.1038/s43016-021-00358-x. hdl:2164/18207 (英语). News article: Meat accounts for nearly 60% of all greenhouse gases from food production, study finds. The Guardian. 2021-09-13 [2022-05-27]. (原始内容存档于2023-10-07) (英语).

- ^ Manceron, Stéphane; Ben-Ari, Tamara; Dumas, Patrice. Feeding proteins to livestock: Global land use and food vs. feed competition. OCL. July 2014, 21 (4): D408. ISSN 2272-6977. doi:10.1051/ocl/2014020

.

.

- ^ 16.00 16.01 16.02 16.03 16.04 16.05 16.06 16.07 16.08 16.09 16.10 Parlasca, Martin C.; Qaim, Matin. Meat Consumption and Sustainability. Annual Review of Resource Economics. 2022-10-05, 14: 17–41 [2023-12-11]. ISSN 1941-1340. doi:10.1146/annurev-resource-111820-032340. (原始内容存档于2022-11-03).

- ^ Steinfeld, H.; Opio, C. The availability of feeds for livestock: Competition with human consumption in present world (PDF). Advances in Animal Biosciences. 2010, 1 (2): 421 [2023-12-11]. doi:10.1017/S2040470010000488

. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2022-10-25) (英语).

. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2022-10-25) (英语).

- ^ What is the Global Land Squeeze?. Land & Carbon Lab. [2022-05-27]. (原始内容存档于2023-02-15).

- ^ Hanson, Craig; Ranganathan, Janet. How to Manage the Global Land Squeeze? Produce, Protect, Reduce, Restore. 2022-02-14 [2022-05-27]. (原始内容存档于2023-09-27) (英语).

- ^ Wang, George C. Go vegan, save the planet. CNN. 2017-04-09 [2019-08-25]. (原始内容存档于2020-11-14).

- ^ Liotta, Edoardo. Feeling Sad About the Amazon Fires? Stop Eating Meat. Vice. 2019-08-23 [2019-08-25]. (原始内容存档于2019-08-24).

- ^ 22.0 22.1 Steinfeld, Henning; Gerber, Pierre; Wassenaar, T. D.; Castel, Vincent. Livestock's Long Shadow: Environmental Issues and Options. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2006 [2008-08-19]. ISBN 978-92-5-105571-7. (原始内容存档于2008-07-26).

- ^ 23.0 23.1 Margulis, Sergio. Causes of Deforestation of the Brazilian Amazon (PDF). World Bank Working Paper No. 22 (Washington D.C.: The World Bank). 2004: 9 [2008-09-04]. ISBN 0-8213-5691-7. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于September 10, 2008).

- ^ Walker, Polly; Rhubart-Berg, Pamela; McKenzie, Shawn; Kelling, Kristin; Lawrence, Robert S. Public health implications of meat production and consumption. Public Health Nutrition. June 2005, 8 (4): 348–356. ISSN 1475-2727. PMID 15975179. S2CID 59196. doi:10.1079/PHN2005727 (英语).

- ^ Hafez, Hafez M.; Attia, Youssef A. Challenges to the Poultry Industry: Current Perspectives and Strategic Future After the COVID-19 Outbreak. Frontiers in Veterinary Science. 2020, 7: 516. ISSN 2297-1769. PMC 7479178

. PMID 33005639. doi:10.3389/fvets.2020.00516

. PMID 33005639. doi:10.3389/fvets.2020.00516  .

.

- ^ Greger, Michael. Primary Pandemic Prevention. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine. September 2021, 15 (5): 498–505. ISSN 1559-8276. PMC 8504329

. PMID 34646097. S2CID 235503730. doi:10.1177/15598276211008134 (英语).

. PMID 34646097. S2CID 235503730. doi:10.1177/15598276211008134 (英语).

- ^ Mehdi, Youcef; Létourneau-Montminy, Marie-Pierre; Gaucher, Marie-Lou; Chorfi, Younes; Suresh, Gayatri; Rouissi, Tarek; Brar, Satinder Kaur; Côté, Caroline; Ramirez, Antonio Avalos; Godbout, Stéphane. Use of antibiotics in broiler production: Global impacts and alternatives. Animal Nutrition. 1 June 2018, 4 (2): 170–178. ISSN 2405-6545. PMC 6103476

. PMID 30140756. doi:10.1016/j.aninu.2018.03.002 (英语).

. PMID 30140756. doi:10.1016/j.aninu.2018.03.002 (英语).

- ^ Bradford, E. (Task Force Chair). 1999. Animal agriculture and global food supply. Task Force Report No. 135. Council for Agricultural Science and Technology. 92 pp.

- ^ Devlin, Hannah. Rising global meat consumption 'will devastate environment'. The Guardian. 2018-07-19 [2018-07-21]. (原始内容存档于2018-07-20).

- ^ Godfray, H. Charles J.; Aveyard, Paul; et al. Meat consumption, health, and the environment. Science. 2018, 361 (6399) [2023-12-11]. PMID 30026199. S2CID 49895246. doi:10.1126/science.aam5324. (原始内容存档于2023-10-12).

- ^ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 Carrington, Damian. Huge reduction in meat-eating 'essential' to avoid climate breakdown. The Guardian. 2018-10-10 [2017-10-16]. (原始内容存档于2019-04-21).

- ^ Schiermeier, Quirin. Eat less meat: UN climate change report calls for change to human diet. Nature. 2019-08-08 [2019-08-09]. (原始内容存档于2019-08-09).

- ^ Holmes, Bob. How much meat can we eat — sustainably?. Knowable Magazine (Annual Reviews). 2022-08-18 [2022-11-09]. S2CID 251688268. doi:10.1146/knowable-081722-1. (原始内容存档于2022-11-28) (英语).

- ^ Damian Carrington, "Avoiding meat and dairy is ‘single biggest way’ to reduce your impact on Earth " (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆), The Guardian, 2018-05-31 (page visited on 2018-08-19).

- ^ Devlin, Hannah. Rising global meat consumption 'will devastate environment'. The Guardian. 2018-07-19 [July 21, 2018]. (原始内容存档于2018-07-20).

- ^ Godfray, H. Charles J.; Aveyard, Paul; et al. Meat consumption, health, and the environment. Science. 2018, 361 (6399) [2023-12-11]. Bibcode:2018Sci...361M5324G. PMID 30026199. S2CID 49895246. doi:10.1126/science.aam5324

. (原始内容存档于2023-10-12).

. (原始内容存档于2023-10-12).

- ^ 37.0 37.1 37.2 FAO. 2006. World agriculture: towards 2030/2050. Prospects for food, nutrition, agriculture and major commodity groups. Interim report. Global Perspectives Unit, United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. 71 pp.

- ^ Nibert, David. Origins and Consequences of the Animal Industrial Complex. Steven Best; Richard Kahn; Anthony J. Nocella II; Peter McLaren (编). The Global Industrial Complex: Systems of Domination. Rowman & Littlefield. 2011: 208 [2023-12-11]. ISBN 978-0739136980. (原始内容存档于2021-09-05).

- ^ Ritchie, Hannah; Roser, Max. Meat and Dairy Production. Our World in Data. 2017-08-25 [2023-12-11]. (原始内容存档于2021-02-19).

- ^ 40.0 40.1 Information About Soya, Soybeans. 2011-10-16 [2019-11-11]. (原始内容存档于2011-10-16).

- ^ Fadel, J. G. Quantitative analyses of selected plant by-product feedstuffs, a global perspective. Animal Feed Science and Technology. 1999-06-30, 79 (4): 255–268. ISSN 0377-8401. doi:10.1016/S0377-8401(99)00031-0 (英语).

- ^ Schingoethe, David J. Byproduct Feeds: Feed Analysis and Interpretation. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Food Animal Practice. 1991-07-01, 7 (2): 577–584. ISSN 0749-0720. PMID 1654177. doi:10.1016/S0749-0720(15)30787-8 (英语).

- ^ 43.0 43.1 43.2 43.3 43.4 Mottet, A.; de Haan, C.; Falcucci, A.; Tempio, G.; Opio, C.; Gerber, P. More fuel for the food/feed debate. FAO. 2022 [2023-12-11]. (原始内容存档于2024-02-26).

- ^ 44.0 44.1 44.2 44.3 44.4 Mottet, Anne; de Haan, Cees; Falcucci, Alessandra; Tempio, Giuseppe; Opio, Carolyn; Gerber, Pierre. Livestock: On our plates or eating at our table? A new analysis of the feed/food debate. Global Food Security. Food Security Governance in Latin America. 2017-09-01, 14: 1–8 [2023-12-11]. ISSN 2211-9124. doi:10.1016/j.gfs.2017.01.001. (原始内容存档于2018-01-30) (英语).

- ^ Borsari, Bruno; Kunnas, Jan, Leal Filho, Walter; Azul, Anabela Marisa; Brandli, Luciana; özuyar, Pinar Gökçin , 编, Agriculture Production and Consumption, Responsible Consumption and Production, Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 2020: 1–11 [2023-02-20], ISBN 978-3-319-95726-5, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-95726-5_78 (英语)

- ^ Zheng, Zhihao; Henneberry, Shida Rastegari. The Impact of Changes in Income Distribution on Current and Future Food Demand in Urban China. Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics. 2010, 35 (1): 51–71 [2023-12-11]. ISSN 1068-5502. JSTOR 23243036. (原始内容存档于2023-10-12).

- ^ Elferink, E. V.; et al. Feeding livestock food residue and the consequences for the environmental impact of meat. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16 (12): 1227–1233. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2007.06.008.

- ^ Hoffman, L. and A. Baker. 2010. Market issues and prospects for U.S. distillers' grains supply, use, and price relationships. USDA FDS-10k-01

- ^ National Research Council. 2000. Nutrient Requirements of Beef Cattle. National Academy Press.

- ^ Anderson, D. C. Use of cereal residues in beef cattle production systems. J. Anim. Sci. 1978, 46 (3): 849–861. doi:10.2527/jas1978.463849x.

- ^ Males, J. R. Optimizing the utilization of cereal crop residues for beef cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 1987, 65 (4): 1124–1130. doi:10.2527/jas1987.6541124x.

- ^ Ward, J. K. Utilization of corn and grain sorghum residues in beef cow forage systems. J. Anim. Sci. 1978, 46 (3): 831–840. doi:10.2527/jas1978.463831x.

- ^ Klopfenstein, T.; et al. Corn residues in beef production systems. J. Anim. Sci. 1987, 65 (4): 1139–1148. doi:10.2527/jas1987.6541139x.

- ^ 54.0 54.1 54.2 Nemecek, T.; Poore, J. Reducing food's environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science. 2018-06-01, 360 (6392): 987–992. Bibcode:2018Sci...360..987P. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 29853680. doi:10.1126/science.aaq0216

.

.

- ^ Merrill, Dave; Leatherby, Lauren. Here's How America Uses Its Land. Bloomberg.com. 2018-07-31 [2019-11-11]. (原始内容存档于2020-02-25).

- ^ Agricultural land (% of land area) | Data. data.worldbank.org. [2023-01-13]. (原始内容存档于2019-05-30).

- ^ Arable land (% of land area) | Data. data.worldbank.org. [2023-01-13]. (原始内容存档于2023-11-07).

- ^ Wang, George C. Go vegan, save the planet. CNN. 2017-04-09 [2019-08-25]. (原始内容存档于2020-11-14).

- ^ Liotta, Edoardo. Feeling Sad About the Amazon Fires? Stop Eating Meat. Vice. 2019-08-23 [2019-08-25]. (原始内容存档于2019-08-24).

- ^ Erb KH, Lauk C, Kastner T, Mayer A, Theurl MC, Haberl H. Exploring the biophysical option space for feeding the world without deforestation. Nature Communications. 2016-04-19, 7: 11382. Bibcode:2016NatCo...711382E. PMC 4838894

. PMID 27092437. doi:10.1038/ncomms11382.

. PMID 27092437. doi:10.1038/ncomms11382.

- ^ Grazing with trees. A silvopastoral approach to managing and restoring drylands. Rome: FAO. 2022. ISBN 978-92-5-136956-2. S2CID 252636900. doi:10.4060/cc2280en. hdl:2078.1/267328.

- ^ 62.0 62.1 Velasco-Muñoz, Juan F. Sustainable Water Use in Agriculture: A Review of Worldwide Research. Sustainability. 2018-04-05, 10 (4): 1084. ISSN 2071-1050. doi:10.3390/su10041084

. hdl:10835/7355

. hdl:10835/7355  (英语).

(英语).

- ^ 63.0 63.1 Kenny, J. F. et al. 2009. Estimated use of water in the United States in 2005 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆), US Geological Survey Circular 1344. 52 pp.

- ^ Zering, K. D., T. J. Centner, D. Meyer, G. L. Newton, J. M. Sweeten and S. Woodruff.2012. Water and land issues associated with animal agriculture: a U.S. perspective. CAST Issue Paper No. 50. Council for Agricultural Science and Technology, Ames, Iowa. 24 pp.

- ^ Konikow, L. W. 2013. Groundwater depletion in the United States (1900-2008). United States Geological Survey. Scientific Investigations Report 2013-5079. 63 pp.

- ^ 66.0 66.1 USDA. 2011. USDA Agricultural Statistics 2011.

- ^ USDA 2010. 2007 Census of agriculture. AC07-SS-1. Farm and ranch irrigation survey (2008). Volume 3, Special Studies. Part 1. (Issued 2009, updated 2010.) 209 pp. + appendices. Tables 1 and 28.

- ^ 68.0 68.1 USDA. 2009. 2007 Census of Agriculture. United States Summary and State Data. Vol. 1. Geographic Area Series. Part 51. AC-07-A-51. 639 pp. + appendices. Table 1.

- ^ HA 730-C High Plains aquifer. Ground Water Atlas of the United States. Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Utah. United States Geological Survey. [2018-10-13]. (原始内容存档于2023-10-12).

- ^ Richter, Brian D.; Bartak, Dominique; Caldwell, Peter; Davis, Kyle Frankel; Debaere, Peter; Hoekstra, Arjen Y.; Li, Tianshu; Marston, Landon; McManamay, Ryan; Mekonnen, Mesfin M.; Ruddell, Benjamin L. Water scarcity and fish imperilment driven by beef production. Nature Sustainability. 2020-03-02, 3 (4): 319–328 [2023-12-11]. ISSN 2398-9629. S2CID 211730442. doi:10.1038/s41893-020-0483-z. (原始内容存档于2023-11-15) (英语).

- ^ Borunda, Alejandra. How beef eaters in cities are draining rivers in the American West. National Geographic. 2020-03-02 [2020-04-27]. (原始内容存档于2020-12-01).

- ^ 72.0 72.1 Xiao, Zhengyan; Yao, Meiqin; Tang, Xiaotong; Sun, Luxi. Identifying critical supply chains: An input-output analysis for Food-Energy-Water Nexus in China. Ecological Modelling. 2019-01-01, 392: 31–37. ISSN 0304-3800. S2CID 92222220. doi:10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2018.11.006.

- ^ Fabrique [merken, design & interactie. Water footprint of crop and animal products: a comparison. waterfootprint.org. [2023-01-13]. (原始内容存档于2024-01-18) (英语).

- ^ Livestock and the Environment. [2017-06-07]. (原始内容存档于2019-01-29).

- ^ the US Code of Federal Regulations 40 CFR 122.42(e)

- ^ United States Environmental Protection Agency. Appendix to EPA ICR 1989.06: Supporting Statement for the Information Collection Request for NPDES and ELG Regulatory Revisions for Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (Final Rule)

- ^ the US EPA. National Enforcement Initiative: Preventing animal waste from contaminating surface and groundwater. http://www2.epa.gov/enforcement/national-enforcement-initiative-preventing-animal-waste-contaminating-surface-and-ground#progress (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- ^ 78.0 78.1 Zhou, Yuan; Yang, Hong; Mosler, Hans-Joachim; Abbaspour, Karim C. Factors affecting farmers' decisions on fertilizer use: A case study for the Chaobai watershed in Northern China. Consilience. 2010, (4): 80–102 [2023-12-11]. ISSN 1948-3074. JSTOR 26167133. (原始内容存档于2023-10-12).

- ^ HERNÁNDEZ, DANIEL L.; VALLANO, DENA M.; ZAVALETA, ERIKA S.; TZANKOVA, ZDRAVKA; PASARI, JAE R.; WEISS, STUART; SELMANTS, PAUL C.; MOROZUMI, CORINNE. Nitrogen Pollution Is Linked to US Listed Species Declines. BioScience. 2016, 66 (3): 213–222. ISSN 0006-3568. JSTOR 90007566. doi:10.1093/biosci/biw003

.

.

- ^ Berger, Jamie. How Black North Carolinians pay the price for the world’s cheap bacon. Vox. 2022-04-01 [2023-11-30]. (原始内容存档于2024-02-27) (英语).

- ^ Merchant, James A.; Naleway, Allison L.; Svendsen, Erik R.; Kelly, Kevin M.; Burmeister, Leon F.; Stromquist, Ann M.; Taylor, Craig D.; Thorne, Peter S.; Reynolds, Stephen J.; Sanderson, Wayne T.; Chrischilles, Elizabeth A. Asthma and Farm Exposures in a Cohort of Rural Iowa Children. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2005, 113 (3): 350–356. PMC 1253764

. PMID 15743727. doi:10.1289/ehp.7240.

. PMID 15743727. doi:10.1289/ehp.7240.

- ^ Borrell, Brendan. In California's Fertile Valley, a Bumper Crop of Air Pollution. Undark. 2018-12-03 [2019-09-27]. (原始内容存档于2019-09-27) (美国英语).

- ^ George, Maureen; Bruzzese, Jean-Marie; Matura, Lea Ann. Climate Change Effects on Respiratory Health: Implications for Nursing. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2017, 49 (6): 644–652. PMID 28806469. doi:10.1111/jnu.12330

.

.

- ^ Viegas, S.; Faísca, V. M.; Dias, H.; Clérigo, A.; Carolino, E.; Viegas, C. Occupational Exposure to Poultry Dust and Effects on the Respiratory System in Workers. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part A. 2013, 76 (4–5): 230–239. PMID 23514065. S2CID 22558834. doi:10.1080/15287394.2013.757199.

- ^ Radon, Katja; Schulze, Anja; Ehrenstein, Vera; Van Strien, Rob T.; Praml, Georg; Nowak, Dennis. Environmental Exposure to Confined Animal Feeding Operations and Respiratory Health of Neighboring Residents. Epidemiology. 2007, 18 (3): 300–308. PMID 17435437. S2CID 15905956. doi:10.1097/01.ede.0000259966.62137.84.

- ^ Schinasi, Leah; Horton, Rachel Avery; Guidry, Virginia T.; Wing, Steve; Marshall, Stephen W.; Morland, Kimberly B. Air Pollution, Lung Function, and Physical Symptoms in Communities Near Concentrated Swine Feeding Operations. Epidemiology. 2011, 22 (2): 208–215. PMC 5800517

. PMID 21228696. doi:10.1097/ede.0b013e3182093c8b.

. PMID 21228696. doi:10.1097/ede.0b013e3182093c8b.

- ^ Mirabelli, M. C.; Wing, S.; Marshall, S. W.; Wilcosky, T. C. Asthma Symptoms Among Adolescents Who Attend Public Schools That Are Located Near Confined Swine Feeding Operations. Pediatrics. 2006, 118 (1): e66–e75. PMC 4517575

. PMID 16818539. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-2812.

. PMID 16818539. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-2812.

- ^ Pavilonis, Brian T.; Sanderson, Wayne T.; Merchant, James A. Relative exposure to swine animal feeding operations and childhood asthma prevalence in an agricultural cohort. Environmental Research. 2013, 122: 74–80. Bibcode:2013ER....122...74P. PMC 3980580

. PMID 23332647. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2012.12.008.

. PMID 23332647. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2012.12.008.

- ^ Müller-Suur, C.; Larsson, K.; Malmberg, P.; Larsson, P.H. Increased number of activated lymphocytes in human lung following swine dust inhalation. European Respiratory Journal. 1997, 10 (2): 376–380. PMID 9042635. doi:10.1183/09031936.97.10020376

.

.

- ^ Areal, Ashtyn Tracey; Zhao, Qi; Wigmann, Claudia; Schneider, Alexandra; Schikowski, Tamara. The effect of air pollution when modified by temperature on respiratory health outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Science of The Total Environment. 2022-03-10, 811: 152336. ISSN 0048-9697. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.152336 (英语).

- ^ Cooke, Christina. NC GOP Protects Factory Farms' Right to Pollute. Civil Eats. 2017-05-09 [2023-11-30]. (原始内容存档于2024-02-22) (英语).

- ^ Canning, P., A. Charles, S. Huang, K. R. Polenske, and A Waters. 2010. Energy use in the U.S. food system. USDA Economic Research Service, ERR-94. 33 pp.

- ^ Röös, Elin; Sundberg, Cecilia; Tidåker, Pernilla; Strid, Ingrid; Hansson, Per-Anders. Can carbon footprint serve as an indicator of the environmental impact of meat production?. Ecological Indicators. 2013-01-01, 24: 573–581. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2012.08.004.

- ^ Capper, J. L. The environmental impact of beef production in the United States: 1977 compared with 2007.. J. Animal Sci. 2011, 89 (12): 4249–4261. PMID 21803973. doi:10.2527/jas.2010-3784

.

.

- ^ Erneubare Energien in Deutschland - Rückblick und Stand des Innovationsgeschehens. Bundesministerium fűr Umwelt, Naturschutz u. Reaktorsicherheit. http://www.bmu.de/files/pdfs/allgemin/application/pdf/ibee_gesamt_bf.pdf[永久失效链接]

- ^ Biogas from manure and waste products - Swedish case studies. SBGF; SGC; Gasföreningen. 119 pp. http://www.iea-biogas.net/_download/public-task37/public-member/Swedish_report_08.pdf (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- ^ U.S. Anaerobic Digester (PDF). Agf.gov.bc.ca. 2014-06-02 [2015-03-30]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2015-06-18).

- ^ NRCS. 2007. An analysis of energy production costs from anaerobic digestion systems on U.S. livestock production facilities. US Natural Resources Conservation Service. Tech. Note 1. 33 pp.

- ^ Ramirez, Jerome; McCabe, Bernadette; Jensen, Paul D.; Speight, Robert; Harrison, Mark; van den Berg, Lisa; O'Hara, Ian. Wastes to profit: a circular economy approach to value-addition in livestock industries. Animal Production Science. 2021, 61 (6): 541 [2023-12-11]. S2CID 233881148. doi:10.1071/AN20400

. (原始内容存档于2023-03-27).

. (原始内容存档于2023-03-27).

- ^ Mitigation of Climate Change: Full report (报告). IPCC Sixth Assessment Report. 7.3.2.1 page 771. 2022 [2023-12-11]. (原始内容存档于2024-02-23).

- ^ Mitigation of Climate Change: Technical Summary (报告). IPCC Sixth Assessment Report. TS.5.6.2. 2022 [2023-12-11]. (原始内容存档于2024-02-23).

- ^ Eisen, Michael B.; Brown, Patrick O. Rapid global phaseout of animal agriculture has the potential to stabilize greenhouse gas levels for 30 years and offset 68 percent of CO2 emissions this century. PLOS Climate. 2022-02-01, 1 (2): e0000010. ISSN 2767-3200. S2CID 246499803. doi:10.1371/journal.pclm.0000010

(英语).

(英语).

- ^ FAO – News Article: Food systems account for more than one-third of global greenhouse gas emissions. www.fao.org. [22 April 2021]. (原始内容存档于2023-09-30) (英语).

- ^ Crippa, M.; Solazzo, E.; Guizzardi, D.; Monforti-Ferrario, F.; Tubiello, F. N.; Leip, A. Food systems are responsible for a third of global anthropogenic GHG emissions. Nature Food. March 2021, 2 (3): 198–209. ISSN 2662-1355. PMID 37117443. doi:10.1038/s43016-021-00225-9

(英语).

(英语).

- ^ Xu, Xiaoming; Sharma, Prateek; Shu, Shijie; Lin, Tzu-Shun; Ciais, Philippe; Tubiello, Francesco N.; Smith, Pete; Campbell, Nelson; Jain, Atul K. Global greenhouse gas emissions from animal-based foods are twice those of plant-based foods. Nature Food. September 2021, 2 (9): 724–732. ISSN 2662-1355. PMID 37117472. S2CID 240562878. doi:10.1038/s43016-021-00358-x. hdl:2164/18207

(英语). News article: Meat accounts for nearly 60% of all greenhouse gases from food production, study finds. The Guardian. 2021-09-13 [2022-05-27]. (原始内容存档于2023-10-07) (英语).

(英语). News article: Meat accounts for nearly 60% of all greenhouse gases from food production, study finds. The Guardian. 2021-09-13 [2022-05-27]. (原始内容存档于2023-10-07) (英语).

- ^ Carrington, Damian. Huge reduction in meat-eating 'essential' to avoid climate breakdown. The Guardian. 2018-10-10 [2017-10-16]. (原始内容存档于2019-04-21).

- ^ Gibbens, Sarah. Eating meat has 'dire' consequences for the planet, says report. National Geographic. 2019-01-16 [2019-01-21]. (原始内容存档于2019-01-17).

- ^ Schiermeier, Quirin. Eat less meat: UN climate change report calls for change to human diet. Nature. 2019-08-08 [2019-08-10]. (原始内容存档于2019-08-09).

- ^ Ripple WJ, Wolf C, Newsome TM, Galetti M, Alamgir M, Crist E, Mahmoud MI, Laurance WF. World Scientists' Warning to Humanity: A Second Notice. BioScience. 2017-11-13, 67 (12): 1026–1028. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix125

.

.

- ^ Castonguay, Adam C.; Polasky, Stephen; H. Holden, Matthew; Herrero, Mario; Mason-D’Croz, Daniel; Godde, Cecile; Chang, Jinfeng; Gerber, James; Witt, G. Bradd; Game, Edward T.; A. Bryan, Brett; Wintle, Brendan; Lee, Katie; Bal, Payal; McDonald-Madden, Eve. Navigating sustainability trade-offs in global beef production. Nature Sustainability. March 2023, 6 (3): 284–294 [2023-12-11]. ISSN 2398-9629. S2CID 255638753. doi:10.1038/s41893-022-01017-0. (原始内容存档于2023-02-10) (英语).

- ^ Monteny, Gert-Jan; Bannink, Andre; Chadwick, David. Greenhouse Gas Abatement Strategies for Animal Husbandry, Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment. 2006, 112 (2–3): 163–70. doi:10.1016/j.agee.2005.08.015.

- ^ Bovine genomics project at Genome Canada. [2020-02-04]. (原始内容存档于2019-08-10).

- ^ Canada is using genetics to make cows less gassy. [2023-12-11]. (原始内容存档于2019-07-24).

- ^ Joblin, K. N. Ruminal acetogens and their potential to lower ruminant methane emissions. Australian Journal of Agricultural Research. 1999, 50 (8): 1307. doi:10.1071/AR99004.

- ^ 115.0 115.1 The use of direct-fed microbials for mitigation of ruminant methane emissions: a review. [2023-12-11]. (原始内容存档于2019-05-05).

- ^ 116.0 116.1 Parmar, N. R.; Nirmal Kumar, J. I.; Joshi, C. G. Exploring diet-dependent shifts in methanogen and methanotroph diversity in the rumen of Mehsani buffalo by a metagenomics approach. Frontiers in Life Science. 2015, 8 (4): 371–378. S2CID 89217740. doi:10.1080/21553769.2015.1063550.

- ^ Dalal, R.C.; et al. Nitrous oxide emission from Australian agricultural lands and mitigation options: a review. Australian Journal of Soil Research. 2003, 41 (2): 165–195. S2CID 4498983. doi:10.1071/sr02064.

- ^ Klein, C. A. M.; Ledgard, S. F. Nitrous oxide emissions from New Zealand agriculture – key sources and mitigation strategies. Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems. 2005, 72: 77–85. S2CID 42756018. doi:10.1007/s10705-004-7357-z.

- ^ Gerber, P. J., H. Steinfeld, B. Henderson, A. Mottet, C. Opio, J. Dijkman, A. Falcucci and G. Tempio. 2013. Tackling climate change through livestock - a global assessment of emissions and mitigation opportunities. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome. 115 pp.

- ^ Bilotta, G. S.; Brazier, R. E.; Haygarth, P. M. The impacts of grazing animals on the quality of soils, vegetation, and surface waters in intensively managed grasslands. Advances in Agronomy 94. 2007: 237–280. ISBN 9780123741073. doi:10.1016/s0065-2113(06)94006-1.

|journal=被忽略 (帮助) - ^ Greenwood, K. L.; McKenzie, B. M. Grazing effects on soil physical properties and the consequences for pastures: a review. Austral. J. Exp. Agr. 2001, 41 (8): 1231–1250. doi:10.1071/EA00102.

- ^ Milchunas, D. G.; Lauenroth, W. KI. Quantitative effects of grazing on vegetation and soils over a global range of environments. Ecological Monographs. 1993, 63 (4): 327–366. JSTOR 2937150. doi:10.2307/2937150.

- ^ Olff, H.; Ritchie, M. E. Effects of herbivores on grassland plant diversity (PDF). Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 1998, 13 (7): 261–265 [2023-12-11]. PMID 21238294. doi:10.1016/s0169-5347(98)01364-0. hdl:11370/3e3ec5d4-fa03-4490-94e3-66534b3fe62f. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2023-10-12).

- ^ Environment Canada. 2013. Amended recovery strategy for the Greater Sage-Grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus urophasianus) in Canada. Species at Risk Act, Recovery Strategy Series. 57 pp.

- ^ Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The contributions of livestock species and breeds to ecosystem services (PDF). [2023-12-11]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2023-10-17).

- ^ Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The contributions of livestock species and breeds to ecosystem services (PDF). FAO. 2016 [2021-05-15]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2023-10-17).

- ^ National Research Council. 1994. Rangeland Health. New Methods to Classify, Inventory and Monitor Rangelands. Nat. Acad. Press. 182 pp.

- ^ US BLM. 2004. Proposed Revisions to Grazing Regulations for the Public Lands. FES 04-39

- ^ NRCS. 2009. Summary report 2007 national resources inventory. USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service. 123 pp.

- ^ De Mazancourt, C.; Loreau, M.; Abbadie, L. Grazing optimization and nutrient cycling: when do herbivores enhance plant production?. Ecology. 1998, 79 (7): 2242–2252. S2CID 52234485. doi:10.1890/0012-9658(1998)079[2242:goancw]2.0.co;2.

- ^ Garnett, Tara; Godde, Cécile. Grazed and confused? (PDF). Food Climate Research Network: 64. 2017 [2021-02-11]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2024-01-14).

The non-peer-reviewed estimates from the Savory Institute are strikingly higher – and, for all the reasons discussed earlier (Section 3.4.3), unrealistic.

- ^ Table of Solutions. Project Drawdown. 2020-02-05 [2023-07-23]. (原始内容存档于2020-11-23) (英语).

- ^ Bai, Yongfei; Cotrufo, M. Francesca. Grassland soil carbon sequestration: Current understanding, challenges, and solutions. Science. 2022-08-05, 377 (6606): 603–608 [2023-12-11]. Bibcode:2022Sci...377..603B. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 35926033. S2CID 251349023. doi:10.1126/science.abo2380. (原始内容存档于2023-07-23) (英语).

- ^ Chang, Jinfeng; Ciais, Philippe; Gasser, Thomas; Smith, Pete; Herrero, Mario; Havlík, Petr; Obersteiner, Michael; Guenet, Bertrand; Goll, Daniel S.; Li, Wei; Naipal, Victoria; Peng, Shushi; Qiu, Chunjing; Tian, Hanqin; Viovy, Nicolas. Climate warming from managed grasslands cancels the cooling effect of carbon sinks in sparsely grazed and natural grasslands. Nature Communications. 2021-01-05, 12 (1): 118. Bibcode:2021NatCo..12..118C. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7785734

. PMID 33402687. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-20406-7 (英语).

. PMID 33402687. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-20406-7 (英语).

- ^ Hayek, Matthew N.; Harwatt, Helen; Ripple, William J.; Mueller, Nathaniel D. The carbon opportunity cost of animal-sourced food production on land. Nature Sustainability. January 2021, 4 (1): 21–24 [2023-12-11]. ISSN 2398-9629. S2CID 221522148. doi:10.1038/s41893-020-00603-4. (原始内容存档于2024-02-04) (英语).

- ^ Bauer, A.; Cole, C. V.; Black, A. L. Soil property comparisons in virgin grasslands between grazed and nongrazed management systems. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1987, 51 (1): 176–182. Bibcode:1987SSASJ..51..176B. doi:10.2136/sssaj1987.03615995005100010037x.

- ^ Manley, J. T.; Schuman, G. E.; Reeder, J. D.; Hart, R. H. Rangeland soil carbon and nitrogen responses to grazing. J. Soil Water Cons. 1995, 50: 294–298.

- ^ Franzluebbers, A.J.; Stuedemann, J. A. Surface soil changes during twelve years of pasture management in the southern Piedmont USA. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2010, 74 (6): 2131–2141. Bibcode:2010SSASJ..74.2131F. doi:10.2136/sssaj2010.0034.

- ^ Kebreab, E.; Clark, K.; Wagner-Riddle, C.; France, J. Methane and nitrous oxide emissions from Canadian animal agriculture: A review. Canadian Journal of Animal Science. 2006-06-01, 86 (2): 135–157. ISSN 0008-3984. doi:10.4141/A05-010

(英语).

(英语).

- ^ McDonald, J. M. et al. 2009. Manure use for fertilizer and for energy. Report to Congress. USDA, AP-037. 53pp.

- ^ Livestock Grazing Guidelines for Controlling Noxious weeds in the Western United States (PDF). University of Nevada. [2019-04-24]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2024-02-23).

- ^ Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The contributions of livestock species and breeds to ecosystem services (PDF). [2023-12-11]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2023-10-17).

- ^ Launchbaugh, K. (ed.) 2006. Targeted Grazing: a natural approach to vegetation management and landscape enhancement. American Sheep Industry. 199 pp.

- ^ Damian Carrington, "Humans just 0.01% of all life but have destroyed 83% of wild mammals – study" (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆), The Guardian, 2018-05-21 (page visited on 2018-08-19).

- ^ Baillie, Jonathan; Zhang, Ya-Ping. Space for nature. Science. 2018, 361 (6407): 1051. Bibcode:2018Sci...361.1051B. PMID 30213888. doi:10.1126/science.aau1397

.

.

- ^ Forests. World Resources Institute. [2020-01-24]. (原始内容存档于2021-04-17) (英语).

- ^ Suite 800, 10 G. Street NE; Washington; Dc 20002; Fax +1729-7610, USA / Phone +1729-7600 /. Tackling Global Challenges. World Resources Institute. 2018-05-04 [2020-01-24]. (原始内容存档于2023-06-09) (英语).

- ^ 148.0 148.1 Watts, Jonathan. Human society under urgent threat from loss of Earth's natural life. The Guardian. May 6, 2019 [2019-05-18]. (原始内容存档于2019-06-14).

- ^ McGrath, Matt. Nature crisis: Humans 'threaten 1m species with extinction'. BBC. 2019-05-06 [2019-07-01]. (原始内容存档于2019-06-30).

- ^ Sutter, John D. How to stop the sixth mass extinction. CNN. 2016-12-12 [2017-01-10]. (原始内容存档于2016-12-13).

- ^ Boyle, Louise. US meat industry using 235m pounds of pesticides a year, threatening thousands of at-risk species, study finds. The Independent. 2022-02-22 [2022-02-28]. (原始内容存档于2023-10-12).

- ^ Anderson, E. W.; Scherzinger, R. J. Improving quality of winter forage for elk by cattle grazing. J. Range MGT. 1975, 25 (2): 120–125. JSTOR 3897442. S2CID 53006161. doi:10.2307/3897442. hdl:10150/646985

.

.

- ^ Knowles, C. J. Some relationships of black-tailed prairie dogs to livestock grazing. Great Basin Naturalist. 1986, 46: 198–203.

- ^ Neel. L.A. 1980. Sage Grouse Response to Grazing Management in Nevada. M.Sc. Thesis. Univ. of Nevada, Reno.

- ^ Jensen, C. H.; et al. Guidelines for grazing sheep on rangelands used by big game in winter. J. Range MGT. 1972, 25 (5): 346–352. JSTOR 3896543. S2CID 81449626. doi:10.2307/3896543. hdl:10150/647438

.

.

- ^ Smith, M. A.; et al. Forage selection by mule deer on winter range grazed by sheep in spring. J. Range MGT. 1979, 32 (1): 40–45. JSTOR 3897382. doi:10.2307/3897382. hdl:10150/646509

.

.

- ^ Strassman, B. I. Effects of cattle grazing and haying on wildlife conservation at National Wildlife Refuges in the United States (PDF). Environmental MGT. 1987, 11 (1): 35–44. Bibcode:1987EnMan..11...35S. S2CID 55282106. doi:10.1007/bf01867177. hdl:2027.42/48162.

- ^ Holechek, J. L.; et al. Manipulation of grazing to improve or maintain wildlife habitat. Wildlife Soc. Bull. 1982, 10: 204–210.

- ^ Dirzo, Rodolfo; Ceballos, Gerardo; Ehrlich, Paul R. Circling the drain: the extinction crisis and the future of humanity. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 2022, 377 (1857). PMC 9237743

. PMID 35757873. doi:10.1098/rstb.2021.0378.

. PMID 35757873. doi:10.1098/rstb.2021.0378. The dramatic deforestation resulting from land conversion for agriculture and meat production could be reduced via adopting a diet that reduces meat consumption. Less meat can translate not only into less heat, but also more space for biodiversity . . . Although among many Indigenous populations, meat consumption represents a cultural tradition and a source of protein, it is the massive planetary monopoly of industrial meat production that needs to be curbed

- ^ 160.0 160.1 Pena-Ortiz, Michelle. Linking aquatic biodiversity loss to animal product consumption: A review (PDF). Freshwater and Marine Biology. 2021-07-01: 57 [2023-12-11]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2023-12-03).

- ^ Belsky, A. J.; et al. Survey of livestock influences on stream and riparian ecosystems in the western United States. J. Soil Water Cons. 1999, 54: 419–431.

- ^ Agouridis, C. T.; et al. Livestock grazing management impact on streamwater quality: a review (PDF). Journal of the American Water Resources Association. 2005, 41 (3): 591–606 [2023-12-11]. Bibcode:2005JAWRA..41..591A. S2CID 46525184. doi:10.1111/j.1752-1688.2005.tb03757.x. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2022-12-15).

- ^ Pasture, Rangeland, and Grazing Operations - Best Management Practices | Agriculture | US EPA. Epa.gov. 2006-06-28 [2015-03-30]. (原始内容存档于2015-09-24).

- ^ Grazing management processes and strategies for riparian-wetland areas. (PDF). US Bureau of Land Management: 105. 2006 [2023-12-11]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2020-05-22).

- ^ Williams, C. M. Technologies to mitigate enviromental [sic] impact of swine production. Revista Brasileira de Zootecnia. July 2008, 37 (SPE): 253–259 [2023-12-11]. ISSN 1516-3598. doi:10.1590/S1516-35982008001300029. (原始内容存档于2023-03-27) (英语).

- ^ Key, N. et al. 2011. Trends and developments in hog manure management, 1998-2009. USDA EIB-81. 33 pp.

- ^ 167.0 167.1 Regaldo, Luciana; Gutierrez, María F.; Reno, Ulises; Fernández, Viviana; Gervasio, Susana; Repetti, María R.; Gagneten, Ana M. Water and sediment quality assessment in the Colastiné-Corralito stream system (Santa Fe, Argentina): impact of industry and agriculture on aquatic ecosystems. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 2017-12-22, 25 (7): 6951–6968. ISSN 0944-1344. PMID 29273985. S2CID 3685205. doi:10.1007/s11356-017-0911-4. hdl:11336/58691

.

.

- ^ Ocean acidification. Journal of College Science Teaching. 2012, 41 (4): 12–13 [2023-12-11]. ISSN 0047-231X. JSTOR 43748533. (原始内容存档于2023-10-12).

- ^ DONEY, SCOTT C.; BALCH, WILLIAM M.; FABRY, VICTORIA J.; FEELY, RICHARD A. Ocean Acidification. Oceanography. 2009, 22 (4): 16–25 [2023-12-11]. ISSN 1042-8275. JSTOR 24861020. doi:10.5670/oceanog.2009.93. hdl:1912/3181

. (原始内容存档于2023-10-12).

. (原始内容存档于2023-10-12).

- ^ Johnson, Ashanti; White, Natasha D. Ocean Acidification: The Other Climate Change Issue. American Scientist. 2014, 102 (1): 60–63 [2023-12-11]. ISSN 0003-0996. JSTOR 43707749. doi:10.1511/2014.106.60. (原始内容存档于2023-10-12).

- ^ Fisheries, Food Security, and Climate Change in the Indo-Pacific Region. Sea Change. 2014: 111–121 [2023-12-11]. (原始内容存档于2023-10-12).

- ^ Bousquet-Melou, Alain; Ferran, Aude; Toutain, Pierre-Louis. Prophylaxis & Metaphylaxis in Veterinary Antimicrobial Therapy. Conference: 5TH International Conference on Antimicrobial Agents in Veterinary Medicine (AAVM)At: Tel Aviv, Israel. May 2010 [2023-12-11]. (原始内容存档于2021-05-26) –通过ResearchGate.

- ^ British Veterinary Association, London. BVA policy position on the responsible use of antimicrobials in food producing animals (PDF). May 2019 [2020-03-22]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2020-11-23).

- ^ Massé, Daniel; Saady, Noori; Gilbert, Yan. Potential of Biological Processes to Eliminate Antibiotics in Livestock Manure: An Overview. Animals. 4 April 2014, 4 (2): 146–163. PMC 4494381

. PMID 26480034. S2CID 1312176. doi:10.3390/ani4020146

. PMID 26480034. S2CID 1312176. doi:10.3390/ani4020146  .

.

- ^ Sarmah, Ajit K.; Meyer, Michael T.; Boxall, Alistair B. A. A global perspective on the use, sales, exposure pathways, occurrence, fate and effects of veterinary antibiotics (VAs) in the environment. Chemosphere. 1 October 2006, 65 (5): 725–759. Bibcode:2006Chmsp..65..725S. PMID 16677683. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.03.026.

- ^ Kumar, Kuldip; C. Gupta, Satish; Chander, Yogesh; Singh, Ashok K. Antibiotic Use in Agriculture and Its Impact on the Terrestrial Environment. Advances in Agronomy. 2005-01-01, 87: 1–54. ISBN 9780120007851. doi:10.1016/S0065-2113(05)87001-4.

- ^ Boeckel, Thomas P. Van; Glennon, Emma E.; Chen, Dora; Gilbert, Marius; Robinson, Timothy P.; Grenfell, Bryan T.; Levin, Simon A.; Bonhoeffer, Sebastian; Laxminarayan, Ramanan. Reducing antimicrobial use in food animals. Science. 29 September 2017, 357 (6358): 1350–1352. Bibcode:2017Sci...357.1350V. PMC 6510296

. PMID 28963240. S2CID 206662316. doi:10.1126/science.aao1495.

. PMID 28963240. S2CID 206662316. doi:10.1126/science.aao1495.

- ^ ESVAC (European Medicines Agency). Sales of veterinary antimicrobial agents in 31 European countries in 2017: Trends from 2010 to 2017 (PDF). October 2019 [2020-03-22]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2021-05-12).

- ^ Boeckel, Thomas P. Van; Pires, João; Silvester, Reshma; Zhao, Cheng; Song, Julia; Criscuolo, Nicola G.; Gilbert, Marius; Bonhoeffer, Sebastian; Laxminarayan, Ramanan. Global trends in antimicrobial resistance in animals in low- and middle-income countries (PDF). Science. 2019-09-20, 365 (6459): eaaw1944 [2023-12-11]. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 31604207. S2CID 202699175. doi:10.1126/science.aaw1944. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2020-05-05) (英语).

- ^ Van Boeckel, Thomas P.; Brower, Charles; Gilbert, Marius; Grenfell, Bryan T.; Levin, Simon A.; Robinson, Timothy P.; Teillant, Aude; Laxminarayan, Ramanan. Global trends in antimicrobial use in food animals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2015, 112 (18): 5649–5654. Bibcode:2015PNAS..112.5649V. PMC 4426470

. PMID 25792457. S2CID 3861749. doi:10.1073/pnas.1503141112

. PMID 25792457. S2CID 3861749. doi:10.1073/pnas.1503141112  .

.

- ^ 181.0 181.1 Bush, Karen; Courvalin, Patrice; Dantas, Gautam; Davies, Julian; Eisenstein, Barry; Huovinen, Pentti; Jacoby, George A.; Kishony, Roy; Kreiswirth, Barry N.; Kutter, Elizabeth; Lerner, Stephen A.; Levy, Stuart; Lewis, Kim; Lomovskaya, Olga; Miller, Jeffrey H.; Mobashery, Shahriar; Piddock, Laura J. V.; Projan, Steven; Thomas, Christopher M.; Tomasz, Alexander; Tulkens, Paul M.; Walsh, Timothy R.; Watson, James D.; Witkowski, Jan; Witte, Wolfgang; Wright, Gerry; Yeh, Pamela; Zgurskaya, Helen I. Tackling antibiotic resistance. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2 November 2011, 9 (12): 894–896. PMC 4206945

. PMID 22048738. S2CID 4048235. doi:10.1038/nrmicro2693.

. PMID 22048738. S2CID 4048235. doi:10.1038/nrmicro2693.

- ^ Tang, Karen L; Caffrey, Niamh P; Nóbrega, Diego; Cork, Susan C; Ronksley, Paul C; Barkema, Herman W; Polachek, Alicia J; Ganshorn, Heather; Sharma, Nishan; Kellner, James D; Ghali, William A. Restricting the use of antibiotics in food-producing animals and its associations with antibiotic resistance in food-producing animals and human beings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Planetary Health. November 2017, 1 (8): e316–e327. PMC 5785333

. PMID 29387833. doi:10.1016/S2542-5196(17)30141-9.

. PMID 29387833. doi:10.1016/S2542-5196(17)30141-9.

- ^ Shallcross, Laura J.; Howard, Simon J.; Fowler, Tom; Davies, Sally C. Tackling the threat of antimicrobial resistance: from policy to sustainable action. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2015-06-05, 370 (1670): 20140082. PMC 4424432

. PMID 25918440. S2CID 39361030. doi:10.1098/rstb.2014.0082.

. PMID 25918440. S2CID 39361030. doi:10.1098/rstb.2014.0082.

- ^ European Medicines Agency. Implementation of the new Veterinary Medicines Regulation in the EU. [2023-12-11]. (原始内容存档于2021-03-06).

- ^ OECD, Paris. Working Party on Agricultural Policies and Markets: Antibiotic Use and Antibiotic Resistance in Food Producing Animals in China. May 2019 [2020-03-22]. (原始内容存档于2021-03-10).

- ^ US Food & Drug Administration. Timeline of FDA Action on Antimicrobial Resistance. Food and Drug Administration. July 2019 [2020-03-22]. (原始内容存档于2021-04-19).

- ^ WHO guidelines on use of medically important antimicrobials in food-producing animals (PDF). [2023-12-11]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2021-04-08).

- ^ European Commission, Brussels. Ban on antibiotics as growth promoters in animal feed enters into effect. December 2005 [2023-12-11]. (原始内容存档于2021-03-09).

- ^ The Judicious Use of Medically Important Antimicrobial Drugs in Food-Producing Animals (PDF). Guidance for Industry. 2012, (#209) [2023-12-11]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2018-11-17).

- ^ Veterinary Feed Directive (VFD) Basics. AVMA. [14 March 2017]. (原始内容存档于2017-04-15).

- ^ University of Nebraska, Lincoln. Veterinary Feed Directive Questions and Answers. UNL Beef. October 2015 [2017-03-14]. (原始内容存档于2019-03-27).

- ^ Lebensmittel aus dem Labor könnten der Umwelt helfen. www.sciencemediacenter.de. [2022-05-16]. (原始内容存档于2022-11-17) (英语).

- ^ Rzymski, Piotr; Kulus, Magdalena; Jankowski, Maurycy; Dompe, Claudia; Bryl, Rut; Petitte, James N.; Kempisty, Bartosz; Mozdziak, Paul. COVID-19 Pandemic Is a Call to Search for Alternative Protein Sources as Food and Feed: A Review of Possibilities. Nutrients. January 2021, 13 (1): 150. ISSN 2072-6643. PMC 7830574

. PMID 33466241. doi:10.3390/nu13010150

. PMID 33466241. doi:10.3390/nu13010150  (英语).

(英语).

- ^ 194.0 194.1 Onwezen, M. C.; Bouwman, E. P.; Reinders, M. J.; Dagevos, H. A systematic review on consumer acceptance of alternative proteins: Pulses, algae, insects, plant-based meat alternatives, and cultured meat. Appetite. 2021-04-01, 159: 105058. ISSN 0195-6663. PMID 33276014. S2CID 227242500. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2020.105058 (英语).

- ^ Humpenöder, Florian; Bodirsky, Benjamin Leon; Weindl, Isabelle; Lotze-Campen, Hermann; Linder, Tomas; Popp, Alexander. Projected environmental benefits of replacing beef with microbial protein. Nature. May 2022, 605 (7908): 90–96. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 35508780. S2CID 248526001. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-04629-w (英语).

News article: Replacing some meat with microbial protein could help fight climate change. Science News. 2022-05-05 [2022-05-27]. (原始内容存档于2023-12-03). - ^ Lab-grown meat and insects 'good for planet and health'. BBC News. 2022-04-25 [2022-04-25]. (原始内容存档于2024-02-20).

- ^ Mazac, Rachel; Meinilä, Jelena; Korkalo, Liisa; Järviö, Natasha; Jalava, Mika; Tuomisto, Hanna L. Incorporation of novel foods in European diets can reduce global warming potential, water use and land use by over 80%. Nature Food. 2022-04-25, 3 (4): 286–293 [2022-04-25]. doi:10.1038/s43016-022-00489-9. hdl:10138/348140. (原始内容存档于2024-01-19).

- ^ Leger, Dorian; Matassa, Silvio; Noor, Elad; Shepon, Alon; Milo, Ron; Bar-Even, Arren. Photovoltaic-driven microbial protein production can use land and sunlight more efficiently than conventional crops. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2021-06-29, 118 (26): e2015025118. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 8255800

. PMID 34155098. S2CID 235595143. doi:10.1073/pnas.2015025118 (英语).

. PMID 34155098. S2CID 235595143. doi:10.1073/pnas.2015025118 (英语).

- ^ Plant-based meat substitutes - products with future potential | Bioökonomie.de. biooekonomie.de. [2022-05-25]. (原始内容存档于2023-12-10) (英语).

- ^ Berlin, Kustrim CerimiKustrim Cerimi studied biotechnology at the Technical University in; biotechnology, is currently doing his PhD He is interested in the broad field of fungal; Artists, Has Collaborated in Various Interdisciplinary Projects with; Artists, Hybrid. Mushroom meat substitutes: A brief patent overview. On Biology. 2022-01-28 [2022-05-25]. (原始内容存档于2023-11-29).

- ^ Lange, Lene. The importance of fungi and mycology for addressing major global challenges*. IMA Fungus. December 2014, 5 (2): 463–471. ISSN 2210-6340. PMC 4329327

. PMID 25734035. S2CID 13755426. doi:10.5598/imafungus.2014.05.02.10.

. PMID 25734035. S2CID 13755426. doi:10.5598/imafungus.2014.05.02.10.

- ^ Gille, Doreen; Schmid, Alexandra. Vitamin B12 in meat and dairy products. Nutrition Reviews. February 2015, 73 (2): 106–115. ISSN 1753-4887. PMID 26024497. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuu011.

- ^ Weston, A. R.; Rogers, R. W.; Althen, T. G. Review: The Role of Collagen in Meat Tenderness. The Professional Animal Scientist. 2002-06-01, 18 (2): 107–111. ISSN 1080-7446. doi:10.15232/S1080-7446(15)31497-2 (英语).

- ^ Ostojic, Sergej M. Eat less meat: Fortifying food with creatine to tackle climate change. Clinical Nutrition. 2020-07-01, 39 (7): 2320. ISSN 0261-5614. PMID 32540181. S2CID 219701817. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2020.05.030 (English).

- ^ Mariotti, François; Gardner, Christopher D. Dietary Protein and Amino Acids in Vegetarian Diets—A Review. Nutrients. 2019-11-04, 11 (11): 2661. ISSN 2072-6643. PMC 6893534

. PMID 31690027. doi:10.3390/nu11112661

. PMID 31690027. doi:10.3390/nu11112661  .

.

- ^ Tsaban, Gal; Meir, Anat Yaskolka; Rinott, Ehud; Zelicha, Hila; Kaplan, Alon; Shalev, Aryeh; Katz, Amos; Rudich, Assaf; Tirosh, Amir; Shelef, Ilan; Youngster, Ilan; Lebovitz, Sharon; Israeli, Noa; Shabat, May; Brikner, Dov; Pupkin, Efrat; Stumvoll, Michael; Thiery, Joachim; Ceglarek, Uta; Heiker, John T.; Körner, Antje; Landgraf, Kathrin; Bergen, Martin von; Blüher, Matthias; Stampfer, Meir J.; Shai, Iris. The effect of green Mediterranean diet on cardiometabolic risk; a randomised controlled trial. Heart. 2021-07-01, 107 (13): 1054–1061. ISSN 1355-6037. PMID 33234670. S2CID 227130240. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2020-317802 (英语).

- ^ Craig, Winston John. Nutrition concerns and health effects of vegetarian diets. Nutrition in Clinical Practice. December 2010, 25 (6): 613–620. ISSN 1941-2452. PMID 21139125. doi:10.1177/0884533610385707.

- ^ Zelman, Kathleen M.; MPH; RD; LD. The Truth Behind the Top 10 Dietary Supplements. WebMD. [2022-06-18]. (原始内容存档于2024-02-27) (英语).

- ^ Neufingerl, Nicole; Eilander, Ans. Nutrient Intake and Status in Adults Consuming Plant-Based Diets Compared to Meat-Eaters: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. January 2022, 14 (1): 29. ISSN 2072-6643. PMC 8746448

. PMID 35010904. doi:10.3390/nu14010029

. PMID 35010904. doi:10.3390/nu14010029  (英语).

(英语).

- ^ Boston, 677 Huntington Avenue; Ma 02115 +1495‑1000. Vitamin K. The Nutrition Source. 2012-09-18 [2022-06-18]. (原始内容存档于2024-01-23) (美国英语).

- ^ Fadnes, Lars T.; Økland, Jan-Magnus; Haaland, Øystein A.; Johansson, Kjell Arne. Estimating impact of food choices on life expectancy: A modeling study. PLOS Medicine. 2022-02-08, 19 (2): e1003889. ISSN 1549-1676. PMC 8824353

. PMID 35134067. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1003889

. PMID 35134067. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1003889  (英语).

(英语).

- ^ Quality of plant-based diet determines mortality risk in Chinese older adults. Nature Aging. March 2022, 2 (3): 197–198 [2022-05-27]. PMID 37118375. S2CID 247307240. doi:10.1038/s43587-022-00178-z. (原始内容存档于2023-10-12) (英语).

- ^ Jafari, Sahar; Hezaveh, Erfan; Jalilpiran, Yahya; Jayedi, Ahmad; Wong, Alexei; Safaiyan, Abdolrasoul; Barzegar, Ali. Plant-based diets and risk of disease mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 2021-05-06, 62 (28): 7760–7772. ISSN 1040-8398. PMID 33951994. S2CID 233867757. doi:10.1080/10408398.2021.1918628.

- ^ Medawar, Evelyn; Huhn, Sebastian; Villringer, Arno; Veronica Witte, A. The effects of plant-based diets on the body and the brain: a systematic review. Translational Psychiatry. 2019-09-12, 9 (1): 226. ISSN 2158-3188. PMC 6742661

. PMID 31515473. doi:10.1038/s41398-019-0552-0 (英语).

. PMID 31515473. doi:10.1038/s41398-019-0552-0 (英语).

- ^ Fortuna, Carolyn. Is It Time To Start Banning Ads For Meat Products?. CleanTechnica. 2022-09-08 [2022-11-01]. (原始内容存档于2023-10-12) (美国英语).

- ^ Pieper, Maximilian; Michalke, Amelie; Gaugler, Tobias. Calculation of external climate costs for food highlights inadequate pricing of animal products. Nature Communications. 2020-12-15, 11 (1): 6117. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.6117P. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7738510

. PMID 33323933. S2CID 229282344. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-19474-6.

. PMID 33323933. S2CID 229282344. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-19474-6.

- ^ Fuso Nerini, Francesco; Fawcett, Tina; Parag, Yael; Ekins, Paul. Personal carbon allowances revisited. Nature Sustainability. December 2021, 4 (12): 1025–1031. ISSN 2398-9629. S2CID 237101457. doi:10.1038/s41893-021-00756-w (英语).

- ^ A blueprint for scaling voluntary carbon markets | McKinsey. www.mckinsey.com. [2022-06-18]. (原始内容存档于2022-09-08).

- ^ These are the UK supermarket items with the worst environmental impact. New Scientist. [2022-09-14].

- ^ Clark, Michael; Springmann, Marco; Rayner, Mike; Scarborough, Peter; Hill, Jason; Tilman, David; Macdiarmid, Jennie I.; Fanzo, Jessica; Bandy, Lauren; Harrington, Richard A. Estimating the environmental impacts of 57,000 food products. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2022-08-16, 119 (33): e2120584119. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 9388151

. PMID 35939701. doi:10.1073/pnas.2120584119

. PMID 35939701. doi:10.1073/pnas.2120584119  (英语).

(英语).

- ^ Towards sustainable food consumption – SAPEA. [2023-06-29]. (原始内容存档于2023-10-01) (英国英语).

- ^ Nicole, Wendee. CAFOs and Environmental Justice: The Case of North Carolina. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2017-03-01, 121 (6): a182–a189. ISSN 0091-6765. PMC 3672924

. PMID 23732659. doi:10.1289/ehp.121-a182.

. PMID 23732659. doi:10.1289/ehp.121-a182.

- ^ Wing, S; Wolf, S. Intensive livestock operations, health, and quality of life among eastern North Carolina residents.. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2017-03-01, 108 (3): 233–238. ISSN 0091-6765. PMC 1637983

. PMID 10706529. doi:10.1289/ehp.00108233.

. PMID 10706529. doi:10.1289/ehp.00108233.

- ^ Thorne, Peter S. Environmental Health Impacts of Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations: Anticipating Hazards—Searching for Solutions. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2017-03-01, 115 (2): 296–297. ISSN 0091-6765. PMC 1817701

. PMID 17384781. doi:10.1289/ehp.8831.

. PMID 17384781. doi:10.1289/ehp.8831.

- ^ Schiffman, S. S.; Miller, E. A.; Suggs, M. S.; Graham, B. G. The effect of environmental odors emanating from commercial swine operations on the mood of nearby residents. Brain Research Bulletin. 1995-01-01, 37 (4): 369–375. ISSN 0361-9230. PMID 7620910. S2CID 4764858. doi:10.1016/0361-9230(95)00015-1.

- ^ Bullers, Susan. Environmental Stressors, Perceived Control, and Health: The Case of Residents Near Large-Scale Hog Farms in Eastern North Carolina. Human Ecology. 2005, 33 (1): 1–16. ISSN 0300-7839. S2CID 144569890. doi:10.1007/s10745-005-1653-3 (英语).

- ^ Horton, Rachel Avery; Wing, Steve; Marshall, Stephen W.; Brownley, Kimberly A. Malodor as a Trigger of Stress and Negative Mood in Neighbors of Industrial Hog Operations. American Journal of Public Health. 2009-11-01, 99 (S3): S610–S615. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 2774199

. PMID 19890165. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2008.148924.

. PMID 19890165. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2008.148924.

- ^ Edwards, Bob. Race, poverty, political capacity and the spatial distribution of swine waste in North Carolina, 1982-1997. NC Geogr. January 2001 [2023-12-11]. (原始内容存档于2022-05-17) (英语).

- ^ FAO's Animal Production and Health Division: Pigs and Environment. www.fao.org. [2017-04-23]. (原始内容存档于2022-04-23).

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||